Using Options Better

A smattering of practical option tips

While a successful volatility trader’s edge is in discerning relative value between options, they are agnostic on the direction of the underlying. This is a niche symbiosis in the ecosystem of markets. The Egyptian plover that cleans the gluttonous gator’s teeth.

The wider, active marketplace, with deeper pools of alpha, sets the price of underlying assets. Fundamental and macro traders have opinion on direction but are agnostic about the price of the options. Just as the vol trader assumes the underlying is “fair”, the directional trader assumes the options are “fair”.

(moontower.ai achievement is bringing a vol trader’s discernment about the relative value of options to the directional trader)

So it doesn’t surprise me that most option users just think of calls and puts as levered directional bets. But an option’s contract is a bundle that prices financing costs, volatility and time. To think of them as firstly as directional tools is to not fully internalize how deep an insight the put-call parity identity is.

The price of an option is primarily about volatility.

[Just look at the decomposition of their p/l equation in A Visual Primer For Understanding Options]

Trading the stock is blunt 2-D expression of a trade. Whether trading the stock directly or an option to express a thesis depends on 2 prerequisites:

- The investor’s perception of the stock’s distribution over some period of time. This is embedded in any decision to click “buy” or “sell”. How explicit any investor’s targets are and what rules they keep for changing their minds spans the gamut from “vibes” to code.

- How that perception differs from the option market

To satisfy #2, you need to be able to interpret the what a vol surface is saying.

- What does the straddle price mean?

- What does a high or low skew mean?

- How do I know if the skew is high or low?

- What does the vol differential between months mean?

- There are so many expiries and strikes, how do I discern which actions on which contracts at what size is the best expression of #1?

Or is the option surface saying that my view is “consensus”? In which case, the only reason to use the options is to sculpt your payoff profile for various scenarios. This exercise makes the trade-offs easily apparent.

[This sounds like a lot but on almost a daily basis I step people through questions like this in the time it takes to have coffee. Half the battle is the options are a second-language problem — and I don’t mean in the jargony sense — I mean it in the I-already-know-the-words-but-I-still-translate-them-instead-of-thinking-in-option-language-natively.

Which is probably why I have a habit of explaining option ideas with my hands automatically. Option sign-language is hockey sticks paths through time embodied.]

Over the years of talking to non-vol traders I have found that option users fall in 2 categories:

- Levered directional players who do not understand that options price volatility and distributions (This discovery peaked during WSB/Reddit heyday and inspired How Options Confuse Directional Traders)

- Investors with an intuitive understanding of options as distributional bets

My grand treatise for group #1 is: Celibacy Vs Condoms: The Answer To Whether You Should Trade Options

For group #2, sit up tall!

You don’t need to have a view that sounds like “this option is priced at 24% vol and I think vol is going to realize 28%”. It’s enough to understand:

- “I’m buying this call because if the stock is up 10% it’s up 20%” (conditional probability of discontinuity)

- The distribution is more bimodal than the option’s market seems to think. One of my favorite examples of this was in The Big Short when the Cornwall guys bought far OTM calls on Capital One because they understood that when the bank was cleared by regulators the stock would be much higher. These were not option guys, but they recognized that the option’s prices didn’t agree with their expected value in what was a discontinuous scenario.

Practical tips

The following ideas are shareable parts of conversations I had with a family office that uses options.

On Risk Budgeting

I was chatting with a family office that uses options (outrights or vertical spreads only) on less than 10% of their trades. They are not vol traders but will use options for 2 reasons:

- “Cornwall” reasoning — they believe the options are mispricing the distribution

- They have a directional view but don’t want to be shaken out of the position due to path.

I’ve addressed #1 above as a great use-case for options. I remind everyone that options are priced for specificity — if you have a variant view of the market, an option is a highly levered exposure to your thesis being exactly right. (Which is why options are the weapon of choice for crooks trading on MNPI. And also why the SEC monitors unusual behavior in single stock options closely.)

#2 is another fitting use for options. I call it managing destination vs path. A small percentage of my trades also fit this pattern. A low delta call that you think is 4-1 to go ITM but if it does you expect it will pay 10 to 1.

This style of trade is called risk budgeting because you decide how much you are willing to lose in advance. “I’m willing to incinerate $1mm on these calls”. When I did such trades, I segregated the risk in an alternate view or what I called the “back book” (careful in the world of pod shops this term means something different — but I was calling it that 15 years when I was on the floor).

You segregate the risk because you don’t want to hedge the gamma or greeks that the option spits off. You’re betting on terminal value not path. If you hedge the gamma you are changing the payoff profile and can now lose more than your initial outlay. [If a stock grinds up to your long strike and expires you will lose the option premium. If you sell shares to hedge the delta the whole way up you lose on all those trades as well].

I asked these investors if they ever roll the OTM calls down if the stock falls? In other words is the terminal value target related to moneyness or absolute price.

What governs their rolling rules?

The answer was basically “feels”.

And I take no issue with that. I’m the last person who is going to condemn a trader for bringing the ineffable interpretation (I prefer “unstructured data”) of various moves into their decision process.

[Discretionary trading has an irreducible amount of “finger in the air”. Will some dolts lean on that as cover for their impulsiveness? Sure. What can I tell you — ambiguity is hard. But over enough reps, your judgement of a trader on a mix of performance and how they narrate their thought process is on more solid footing than your judgement of your primary care physician. Have a sense of proportion.]

The actual they gave was “well, if the stock goes down after we bought the calls we just accept that we were probably wrong and let it go”.

That was a bit head-scratching for me. Like the probability of the stock closing at a price at some point below the price it was when you bought the call is close to 100% (you could re-phrase this as “what’s delta of an at-the-money one-touch put?”).

The answer was a bit too low-res and self-defeating imo. After all, the majority of a stock’s move is systematic risk not “idio”. So the logic just collapses to “if the stock market downticks, we are wrong about this stock”.

I proposed:

What if you normalized the stock’s move by its beta and a confidence interval? So if the stock market is down, but your name is down by much less, than you were actually right on the name. How about test all those cases to see if a rule like

- If market is lower, but stock outperforms then re-strike the option (ie roll the calls down)

There are still messy details like “how often” but this is an example of a wider lesson that I harp on — measurement not prediction. By measuring in absolute terms, you get one answer — “we are wrong”, but in relative terms you could be right. But the logical leap in how to measure comes from understanding reality clearly — every stock move is mostly systematic. It’s part of a basket that by index arbitrage imposes flows in the name based on what the index futures do.

Another thought

There’s an asymmetry to rolling. If you buy a 15 delta put and the stock rallies, vol likely declines. Even if the put skew increases, there’s a good chance that rolling the puts up will feel like a bargain compared to the opposite scenario — where you bought a 15 delta call, the stock falls, vol expands and the call spread you buy to roll down feels rich.

Rolling puts up feels better than rolling calls down.

I come from a tradition that needs to measure everything in pennies. So I might be splitting hairs to a fundamental investor. But it did remind me share something I like to do:

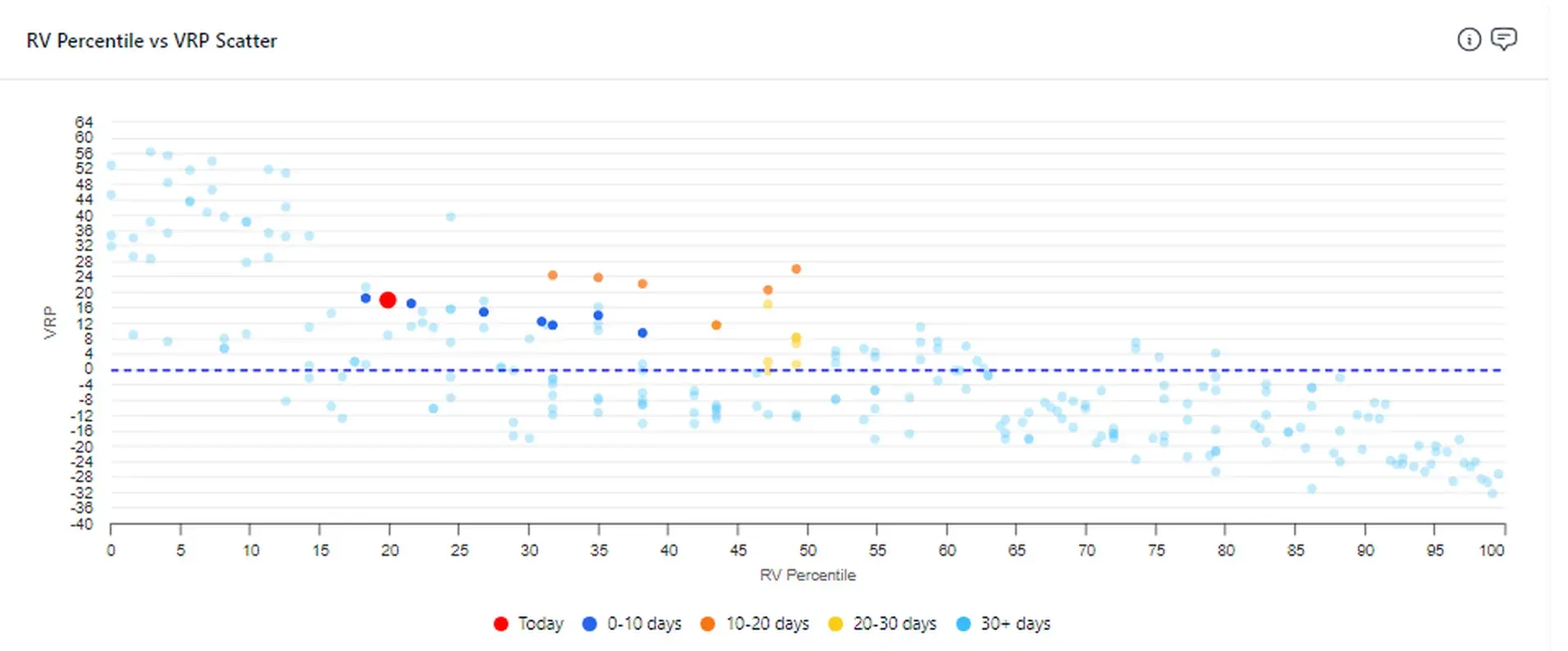

Throw everything in a scatterplot!

What’s the price of a 30d delta/10 delta call spread as a percentage of the spot price for various vol levels. This nets out the impact of ATM vol changing while the skew changes. Vol is lower but the put skew is higher. Ughh, just show me how much premium as a percent of spot that spread costs.

More scatterplot tips

1) Restrict ranges to consider conditional probabilities.

If you fit a regression line between vol level and put skew you will see that skew flattens as vol increases. If you restrict your sample to a regime (say to when SPX vol is sub 10%) that line will be steeper. If you were looking to buy puts, every time vol was cheap, you might be deterred because skew was in the 75th percentile. But maybe that same skew is in the 40th percentile conditional on ATM vol being below 10%?

[I will pull the data and show this picture in another post but I’m writing this off the cuff]

2) Color code the dots to show time

IYR realized vol has been falling and since the VRP ratio has been stable that means a short vol position has the wind at its back as both the IV and RV are declining.

You can hack your way to a lot of intuition by throwing data on scatterplots and jamming a line through it.