how to become the main character on voltwit

when measuring changes in vol as a percent makes sense

A reliable way to have Nassim Taleb come through your window to call you an iiiiidiot is to see a stock crash and say something like “That was a 10-standard deviation move!”

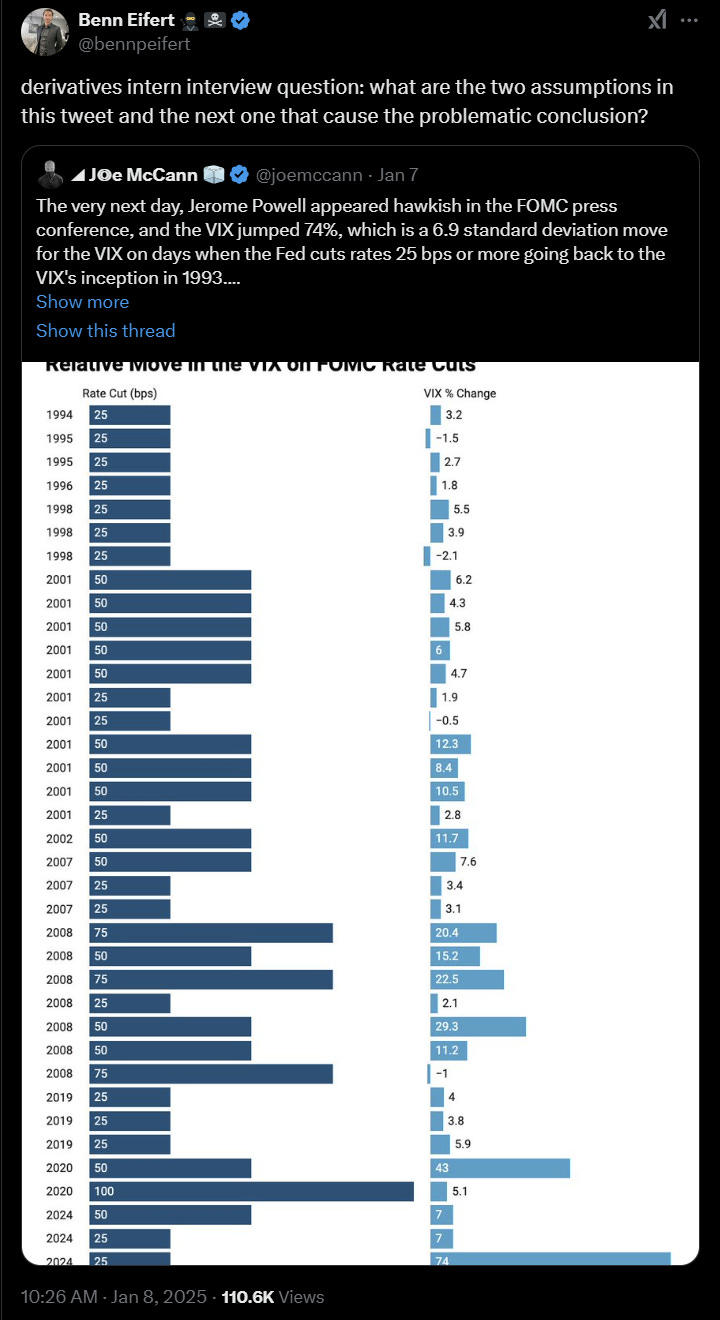

On #voltwit, the corner of fintwit with an option fetish, a surefire way to get QVR’s Benn Eifert to QT you is to quote VIX changes in percent terms.

The topic resurfaces every time VIX makes a large move, voltwit predictably reacts so I figured Grok (X’s LLM chatbot) must know about this.

I asked Grok some questions and sure enough it seems like it’s been paying attention.

“Is it wise to quote VIX changes in percent terms?”

- Volatility of Volatility: The VIX itself is inherently volatile, so small percentage changes might not always reflect significant shifts in market sentiment or conditions.

- Misinterpretation: Large percentage changes from a low base might exaggerate perceived market fear or complacency. Conversely, small percentage changes at high levels might understate the market's condition.

- Contextual Information: Percentages without context (like the baseline level of the VIX) can be misleading. A 5% increase in VIX might mean different things at different times.

“Do vol traders dunk on tourists who quote VIX percent changes?”

In the trading community on platforms like X, there's often a playful or critical banter between experienced volatility (vol) traders and those perceived as "tourists" or less experienced traders.

- Misinterpretation Risks: Vol traders often emphasize that quoting VIX in percentage terms without additional context can lead to misinterpretations. For example, a 10% increase from a very low VIX level might not be as significant as the same percentage increase from an already high level.

Benn’s primary gripe with VIX percents is the behavior of VIX is level-dependent. Its distribution is not congruent at high and low levels of vol.

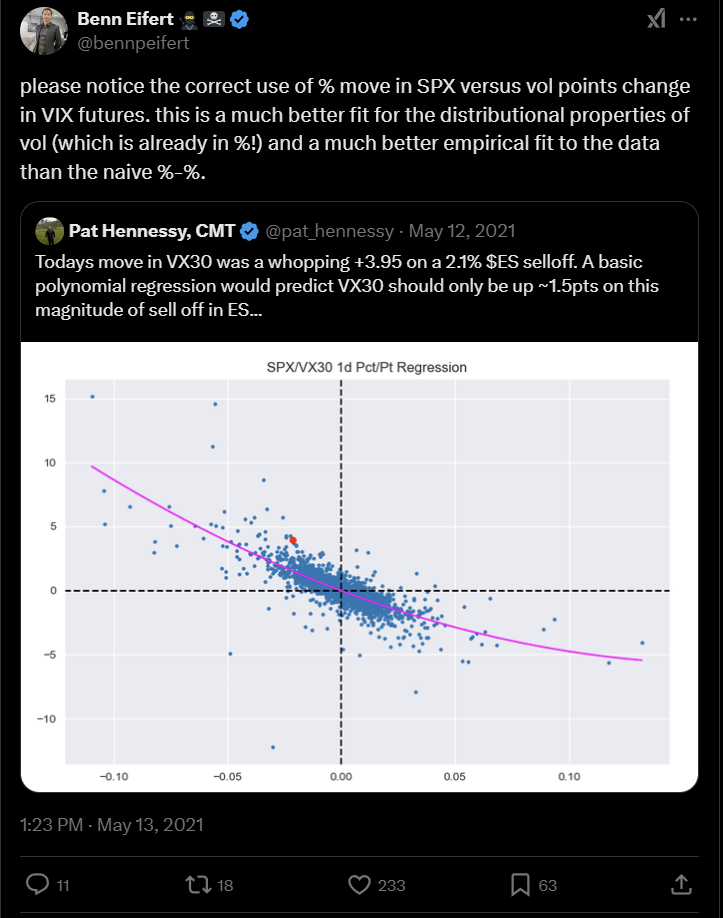

Notice how the Y-axis is VIX vol points not percents.

In chatting with Benn about this article he pointed out a basic mechanic that makes vol level-dependent:

Volatility is inherently about squared returns, so you can have a very low base level of realized vol but all it takes is one big-ish sized return and because we're squaring it (along with all the other little returns in the window) it's going to have a massively outsized impact on window realized volatility. That makes vol very jumpy from low levels.

Another vol manager, Kris Sidial of Ambrus, explains it simply. Note my response below it.

There are multiple contexts in which it is quite useful to measure percent changes in volatility. There are tradeoffs, as you’d expect with any measure. But I’ve always been forceful about the need to slice things from different angles. It’s a healthy way to identify mixed signals, but it’s also affirming when sufficiently different angles agree.

A good example of this “multiple angles” idea is the 2 part series:

- Volatility term structure from multiple angles (I)

- Volatility term structure from multiple angles (II)

Let’s get into a few reasons to measure vol in percent changes.

Cross-sectional comparison

As a relative value options trader, I would typically have an “axe list”. These are vols in various names in various parts of the surface I thought were relatively cheap or expensive.

[The idea of an “axe list” is covered in the Moontower Mission Plan]

Armed with my opinions, I would then buy the options I thought were cheap on days when their strike vols were underperforming, and sell the expensive ones on days the strike vols were outperforming.

Because I’m looking at vols cross-sectionally it makes sense to look at the percent changes in the vol. A one-point move in SPY is much larger than a one-point move in TSLA.

[See Understanding The Vol Scanner for a full explanation.]

Notes and caveats

1) Measuring percent changes in vols work well “locally”.

For example, it was common in modeling spot-vol correlation in oil to assume that as oil futures went up 1%, that vol declined 1%.

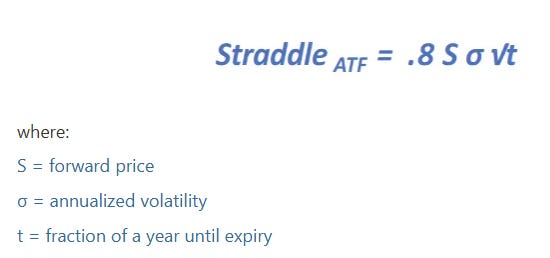

[This dynamic corresponds to a “constant ATM straddle regime”. It is easily visible from the straddle approximation formula.]

But nobody believes that doubling the oil price will suddenly lead to a halving in vol. The model only works “locally.”

2) Percent vol changes can be further refined by normalizing for “vol of vol”

If SPY vol changes from 20% to 21%, a 5% change in vol level might still be more significant than TSLA vol changing from 60% to 63%, also a 5% change, because TSLA vol of vol might be higher. After all, it might be common for TSLA vol to move 5% per day.

The analogy to regular investing would be the difference between a dollar-neutral position and a beta-weighted position. If you are long $100 of TSLA and short $100 of SPY, your portfolio will act like it’s long even though in dollars it’s flat. You are long beta because TSLA is more volatile.

[I’m ignoring the correlation aspect of beta because it’s not central to the argument.]

3) An extra note on “vol of vol”

If you measure vol of vol based on changes in ATM vol you are getting a confounding reading. Like if you measured your pulse with your thumb.

Why?

ATM vols are “floating” strike vols. If SPY drops 1% and ATM vol increases by 1 point, that might just be movement along the vol curve. The vol on the 99% strike might have simply been 1 point higher than the prior day’s 100% strike. On a fixed strike basis, the vol didn’t change. In this case, the appearance of a vol change merely reflected a change in the underlying.

For vol trading purposes, you usually care about fixed strike changes (ie curve shifts not movement along the curve) because that’s what drives the vega p/l of the attribution.

Risk and P/L measurement

The second reason to care about percent changes in vol only applies to vol traders. Vol traders defined as traders who run a delta-neutral book and make their edge from isolating cheap and expensive vol.

That said, the discussion should be highly educational for anyone trying to learn options or as a useful self-test for traders who might be interviewing and expected to talk about managing a book.

Let’s back up to consider vol risk. Specifically, vega, the sensitivity of your option p/l due to changes in implied vol.

We start with a scenario. Assume the ATM and at-the-forward (ATF) strikes are the same.

You buy 100 December ATM straddles in stock A and short 100 December ATM straddles in Stock B.

Stock A and Stock B trade for the same price.

Stock B has 2x the implied vol of Stock A.

Are you vega-neutral?

Are you theta-neutral?

[You can look at the greeks from an option calculator to help but if you are an experienced option trader you shouldn’t need to.]

Ok, let’s get to the answers.

You are vega-neutral. Recall the straddle approximation:

Since vega is just change in option (in this case straddle) price per 1 point change in vol, then:

vega = .8 * S * √t

Look at the formula — ATF vega has no dependence on vol level!

Since S and t are equal then your long and short vega perfectly offset.

[Note: OTM option vega DOES depend on vol level. They have volga or “vol gamma” which is what fuels vol convexity.]

Ok, you’re vega-neutral.

Are you theta-neutral?

Again we don’t need an option model. If Stock B is 2x the vol as Stock A its straddle is 2x the price. If both stocks don’t move until expiry, all options go to zero. Necessarily, Stock B experienced 2x the decay.

If you are short the straddle in Stock B, your portfolio collects theta. It is NOT theta-neutral.

Vol traders will often think in terms of vega. “I bought $50k vega in ABC today”.

At the same time, they often try to run a roughly theta-neutral book.

[See Weighting An Option Pair Trade for a discussion about vega and theta weighting and how the weighting should be matched to the expression of your bet — proportional vs spread].

In the riddle above, being vega-neutral did not mean theta-neutral. But we can actually transform vega so that a vega-neutral position is correlated to a theta-neutral position!

Another way to measure vega: “vega per 1%”

Let’s say the vega per straddle was $.50

If you buy 100 straddles your vega is 100 x $.50 x (100 multiplier) =

$5,000

If vol increases by 1 point you make $5,000 from the change in implied vol.

Assume that the implied vol of the straddle is 25%

Multiply the vega by the vol:

$5,000 x 25% = $1,250

Watch what happens if we raise the vol by 1% or .25 points instead of 1 point:

Vega p/l: $5,000 x .25 points = $1,250

Remember when we raised vol by a full point from 25% to 26% (or a 4% change in the vol) you made $5,000 or $1,250 x 4)

By multiplying the vega by the vol itself we have created a new measure:

Vega per 1% measures the vega p/l per 1% change in the vol.

Let’s return to the original riddle.

We now assign implied vols to the straddle. You are long 100 straddles of Stock A at 25% vol and short 100 straddles of Stock B at 50% vol.

While this is vega neutral, it is NOT vega per 1%-neutral

Stock A “vega per 1%”: +$5,000 x 25% is +$1,250

Stock B “vega per 1%”: -$5,000 x 50% is -$2,500

You are net short $1,250 vega per 1%

This perspective is useful for a few reasons:

1) Linear estimate of p/l with respect to percent changes in vol

If vol is up 3% your p/l is simply 3 x vega per 1%. If you are using a view like “vol scanner” to see all the percent changes in vol cross-sectionally the changes will map easily to your vega per 1% risk

2) Vega per 1% proxies a theta-weighted position which is how vol traders often think about their risk and the idea that they are betting on relative proportional vol changes.

If you are short vega per 1% you are collecting theta

Multiple angles

Looking at vega in both the conventional way (p/l sensitivity per 1 point change in vol) and vega per 1% reveals features of a position.

If you are long vega per 1% but short vega, what does that mean?

Any combination of the following:

- You are short time spreads,

- You are long high vol options and short lower vol options. Owning skew or vol convexity are both examples of this.

- Cross-sectionally you are long high vol names and short low vol.

[Note in all these case it’s possible to be paying theta and short gamma locally. But if you shocked the position in a scenario analysis you likely make a ton of money. The relationships between Greeks are all clues as to what is lurking in a complex portfolio.]

In the riddle scenario, to be flat vega per 1%, you must ratio the trade and be short 1/2 as many high vol straddles. Note you will be net long vega. You will win if all the vols parallel shift higher (ie they all go up 10 points), but if they maintain their .5 relationship the p/l will be flat, consistent with the meaning of flat vega per 1%.

Understanding your greeks means understanding what you’re rooting for. You’d be surprised to know that sometimes option traders don’t even know what they’re rooting for.

When you get down to it, any large percentage change in vol is going to require multiple angles to understand. Your p/l isn’t going to line up because vega itself will change as the underlying changes and vol changes interact. Measuring percent changes on small numbers is usually a bad idea and requires transformations to find divine anything worth mentioning.

Does it make sense to talk about a 75% change in VIX from a base vol of 8%? Of course not. One of the reasons you know that is because it can’t fall 75% from 8%. That’s a clue right there that “standard deviation”, a concept we learned about from symmetrical pictures in HS math texts, is not in charge.

In sum, percent changes in vol can be useful measures but you have to know how to wield them and where they break down.

Unless you want to be the main character on voltwit for a day (and have to fix your broken window). But if you’re ok with that at least go the extra mile and do some technical analysis on VIX.

Final caveat

When you use vega per 1% you implicitly assume that both assets have the same vol of vol. In other words, if a 15% vol name’s IV bounces around 1 vol point per day, then a 30 vol name bounces around 2 vol points per day. This may or may not be true but it’s a better guess than raw vega weighting, which would show being long 100 straddles in A (25% IV) and short 100 straddles in B (50% IV) as flat.