Vol orders and discussion on option execution

A few common misunderstandings

Today is about option execution. It’s a blanket response to a host of misunderstandings I find in talking to investing practitioners who don’t come from the market-making side.

Before that we’ll cover a couple things I found interesting.

Option volume explosion

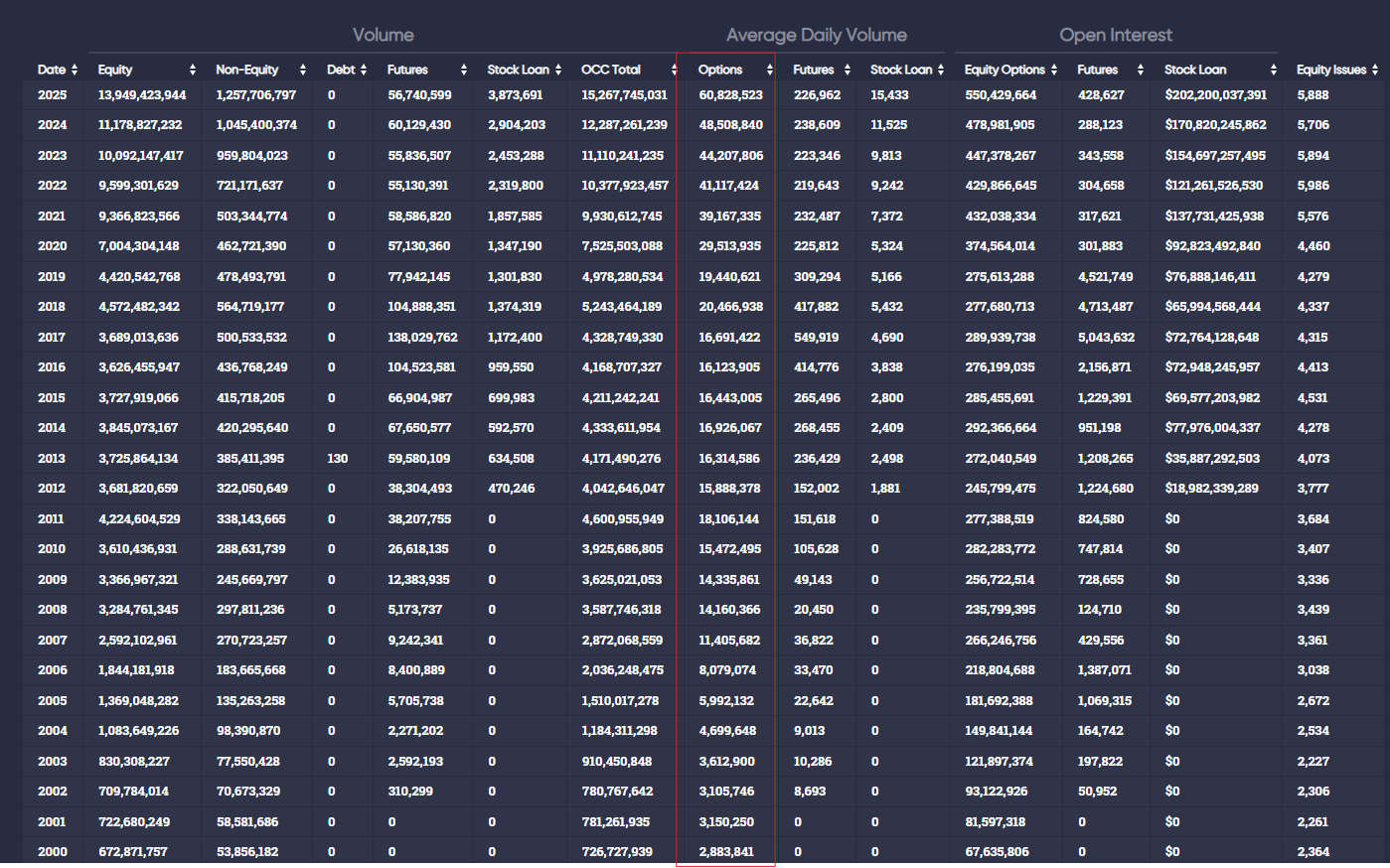

This table is from the OCC:

From 2005-2007 option volume doubled.

It took 13 years, until 2020, to double again.

And just 5 years to double still again.

If you’ve been paying attention to the options world, you know that the last 5 years have seen both a massive increase in retail participation which coincided with the very successful product launch known as 0dte.

A friend with a senior role at a MM has described the last few years as “money raining from the sky”.

Trader Challenges

I loved this post by Rob Carver:

Wordle (TM) and the one simple hack you need to pass funded trader challenges

In fact, I’m going to be meta and write about this post because of its pedagogical value. Rob saw a situation in the wild, turned it into a real-life word problem, and solved it. We’re going to step through what was unsaid because that process would be helpful to learners who want to get better at recognizing the nature of a problem and constructing a solution.

Excerpt from the intro:

There has been some controversy on X/Twitter about ‘pay to play’ prop shops (see this thread and this one) and in particular Raen Trading. It’s fair to say the industry has a bad name, and perhaps this is unfairly tarnishing what may pass for good actors in this space. It’s also perhaps fair to say that many of those criticising these firms, including myself, aren’t as familiar with that part of the trading industry and our ignorance could be problematic.

But putting all that aside, a question I thought I would try and answer is this - How hard is it to actually pass one of these challenges?

The rules of the Raen challenge are this:

- You must make 20%

- You can’t lose more than 2% in a single day. There is no maximum trailing drawdown. So if you lose 1.99% every day forever, you’re still in the game.

- You must trade for at least 30 trading days before passing the challenge

- It costs $300 a month to do the challenge. This isn’t exactly the same Raen which charges a little more, but as a rounder number it makes it easier to directly see how many months we expect to take by backing out from the cost per month. I assume this is paid at the start of the month.

His post is totally free. You should read it. But I want to branch from this point where he laid out the rules of the challenge.

The first thing you need to recognize

To even begin answering the question of how it is to pass the challenge you need to state it in terms of “how hard is it to pass given some [expected daily return] and [volatility]?”

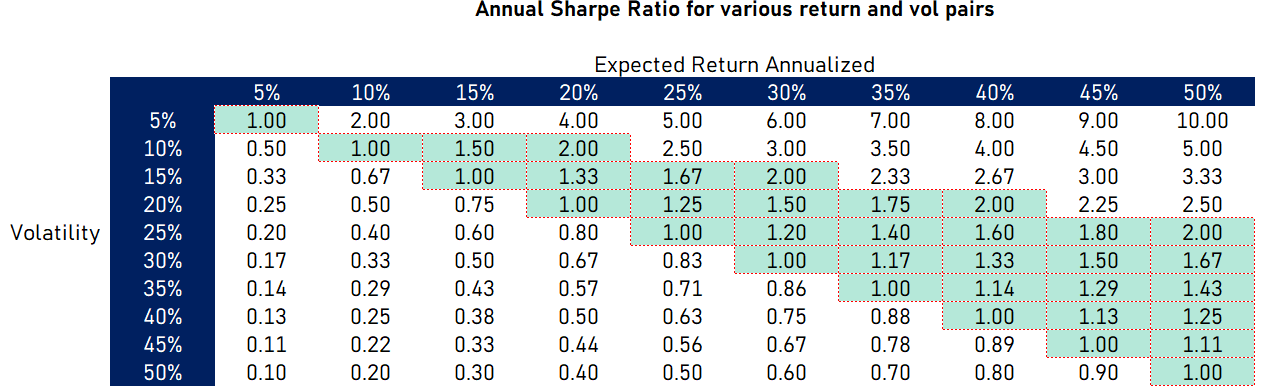

Since the variables of concern are return and volatility, or reward vs risk, the concept of a Sharpe ratio immediately comes to mind.

If you have an expected daily return of 20% with 0% volatility, then your chance of success is obviously 100%. That’s an infinite (undefined?) SR.

If you are even remotely near the investing world you probably have some sense that the SP500 has something like a .5 SR and an SR of something like 2 would be very high. If SP500 is 15% vol, then you are talking about an investment with SP500 vol but gets you 30% per year. You do that for an extended period of time and everyone knows your name.

We can make a reasonable matrix of values for our 2 values of interest.

Since giving a go at trading involves work and buying SPY does not, then having a SR greater than .50 to warrant the effort sounds table stakes. Any number from 1.0 to 2.0 feels like an appropriate starting point, even if it’s arbitrary. Rob starts with 1.5. Fine.

Restating the problem:

If you have a Sharpe Ratio of 1.5 and trade with 15% annual volatility, what’s your chance of passing a funded trader challenge that requires:

- Hitting 20% profit

- Without any single day losing more than 2%

- While paying $300/month

Rob recognizes that this is best solved with a simulation, but that’s actually an enlightened reflex. Let’s not take it for granted.

Could you solve this with math in a closed-form way?

Let’s try to solve this with formulas. What we can assume:

Daily returns ~ Normal(μ, σ) where:

- μ = (SR × Vol) / 252 = (1.5 × 0.15) / 252 = 0.0893% per day

- σ = Vol / √252 = 0.15 / √252 = 0.945% per day

Question 1: How long to reach 20%?

Simple approach: 20% / 0.0893% = 224 days

Hmm. This seems wrong for several reasons:

- You don’t go straight up

- The bust-out rule: any day < -2% resets you

We need to bring volatility and path dependency into consideration. We ask another question.

Question 2: Probability of hitting -2% on any given day?

P(return ≤ -2%) = Φ((−0.02 − 0.000893) / 0.00945) = Φ(−2.21) ≈ 1.4%

This seems useful. Now what?

Question 3: What’s the probability of reaching 20% before hitting -2%?

The lyrics to Steppenwolf’s Pusher come to mind:

tombstones in my eyes

I have no idea how you solve this analytically.

Fortunately, this question comes to mind 5000 years since Indian mathematicians invented Arabic numerals and 3 years since Anthropic released the tireless teacher known as Claude.

It (he? she? they?) says:

This is a "gambler's ruin" problem with two absorbing barriers: +20% (win) and one day at -2% (lose), but after bust-out, you reset to 0% and try again!

He goes on to explain that solving this problem analytically requires:

- Solving partial differential equations (diffusion processes)

- Handling the reset mechanism (not a standard boundary condition)

- Tracking cumulative costs over multiple attempts

- Computing time-dependent probabilities

But Claude, how would I know this stuff?

Oh young Padawan, if you wanted to solve this without simulation, you’d need to learn:

1. Stochastic Calculus

- Brownian motion

- Geometric Brownian motion (for compounding returns)

- Itô’s lemma

- First passage time problems

2. Partial Differential Equations

- Kolmogorov forward/backward equations

- Boundary value problems

- Absorbing barriers and reflecting boundaries

3. Renewal Theory

- For the “reset and try again” mechanism

- Markov renewal processes

- Expected costs with renewal

Estimated Learning Time: 1-2 years of graduate-level probability theory

Oh.

It’s gonna take more effort than watching a Veritasium at 2x speed? Bruh, I don’t have cave time on my hands here.

I assume Rob reacted to this trading challenge word problem like a linebacker diagnosing pass vs run in a split second. This is a problem for simulation.

Anyway, I just thought it would be helpful to explicate the unsaid.

And one las thing. Since Rob was generous enough to post his code, I made Claude work overtime for no pay (inner monologue: does this mean I would’ve owned slaves 400 years ago?). Claude’s yield:

https://trading-sim.moontowermeta.com/

Option execution

While stock execution is a vast topic depending on how finicky you want to be about HFT, microstructure, game theory, counterfactuals, lit vs dark, block trading, etc etc, most institutional algos coalesce around some concept of VWAP or TWAP where the goal is to minimize market impact by making sure you are not an outsize percentage of the volume.

Option execution has no equivalently popular Schelling point benchmark such as a VWAP. This is partly because option premiums are themselves moving targets depending on the interplay of time, implied volatility, and moneyness. This is not a big issue, you could harmonize measurements in any number of ways including by the greeks. You’ll get some sense of how we can do that below. But the fact that you can pay more for an option but be purchasing a lower IV is hint enough that VWAP-ing according to premium is incoherent.

The biggest issue is that the intent of an option order has a different time horizon from a typical stock order. If you are an investor, you probably don’t care that it takes 3 days to accumulate your position as long as there are no catalysts in the execution window. But options, when used as they should be, with a basis in volatility assessment (in other words, discernment of the magnitude of a move over a certain period of time), naturally require more time-sensitive execution.

Options are also less liquid, especially outside the top 50 names or so. Given the sheer number of expiries, strikes and symbols, it is far more likely you are selling the 62 DTE, .24 delta call against a market-maker rather than someone else who woke up that morning thinking they’d like to invest that particular option. This means, you want to minimize your encounters with the order book so even if you could VWAP your order, if the counterparty is a MM you are far more likely to be leaking info that you have an order big enough to make piecing it out worthwhile. This information can and will be used against you.

The best you can do with respect to option execution is not be stupid. Your order is easy to spot. It’s the one whose limit doesn’t tick with the stock (we’ll address counters to this below!). You are always going to lose to your execution in expectation. You can tattoo that on your face. We’ll shed some light on what’s happening on those screens.

Edge functions

At any snapshot in time, market-makers have a fair value for what an option is worth. They stream a bid/ask whose width depends on an “edge function”. The general specification for this function is “how many cents of edge to I need to compensate me for hedging the delta and the vol risk”?

Delta risk

If I believe that buying 100,000 shares of stock XYZ will push it up 8 cents from the current stock offer, then I need to pad my option offer in the .25 delta call by $.02 just to breakeven on expected slippage on selling 1000 options. Note that the offer I’m streaming is not using “last sale” or “mid-market” as the S in the option model. It’s using “stock ask”. The call bid I’m streaming, is using the “stock bid” since I will be selling shares to hedge if I buy calls. You can step through this exercise yourself for put bids and put offers.

Vol risk

Let’s say this same option has a vega of $.10 meaning if IV increases by 1 point, the option premium, all else equal, goes up by $.10.

If this is an asset whose IV moves about 1 point per day, I might be fine accepting something like 1/2 a vol point of edge or $.05 cents to open a position. If the IV moves 10 points a day I’ll demand $.50 per contract to compensate me for the vega risk.

So at the very least, the bid/ask spread reflects the market maker’s willingness to warehouse the vol risk and there cost to hedge at the point of sale. Of course, a multitude of dealers with differing fair values and leans creates a tighter market than if there is only a handful.

If the market is more volatile, then slippage assumptions increase not just becasue the underlying shares are wider, but because there will be less liquidity at each price level. The consumer should expect wider spreads. Volatility itself will also more volatile. Again, wider spreads.

Edge functions are a tax on all option-related strategies when markets get crazy. Including strategies that are biased long vol but generally takers. They still need to trade. Edge functions are like COGs. Market-makers’ costs, including their funding spreads, are passed on to everyone else.

Order types

Like stocks, there are limit and market orders in options. But there is a class of contingent orders that makes sense in light of option premiums being moving targets.

Delta-adjusted orders

A delta-adjusted order may take the form of:

“If the stock is $100.50 bid or higher, I’m willing to offer the 99 put as low as $.50”

You can even peg the offer to the stock bid so that it keeps cancel/replacing according to its delta (so if it is .25 delta, every time the stock drops 4 cents your offer increases a penny) down to some ultimate low premium you’d accept.

You can even “auto-hedge” this type of order. So if you get filled on the puts, it triggers an order to sell or short shares on the bid subject to some tolerance. If the stock moves lower quickly after you sell the puts the auto-hedger will have parameters that you set about how far to “chase”. This is important because you should expect to get filled on the puts when the stock drops quickly and a market-maker snipes your stale offer before your broker has a chance to pull.

In other words, your fills are constant reminders of adverse selection. I’ve explained this in the broader discussion of limit orders:

From Reflections on Getting Filled:

My Bayesian analysis of being filled on a limit order vs market order

Imagine a 1 penny-wide bid/ask.

If you bid for a stock with a limit order your minimum loss is 1/2 the bid-ask spread. Frequently you have just lost half a cent as you only get filled when fair value ticks down by a penny (assuming the market maker needs 1/2 cent edge to trade). But if you are bidding, and super bearish news hits the tape (or god forbid your posting limit orders just before the FOMC or DOE announce economic or oil inventory), your buy might be bad by a dollar before you can read the headline.

If you lift an offer with an aggressive limit (don’t use market order which a computer translates at “fill me at any price” which is something no human has ever meant), then your maximum and most likely loss scenario is 1/2 the bid-ask spread.

Do you see the logical asymmetry conditional on being filled?

Passive bid: best case scenario is losing 1/2 cent

Aggressive bid: worst case scenario is losing 1/2 cent

This is why exchanges offer rebates for posting bids/offers — the payment incentivizes liquidity which nobody would ever offer otherwise because of adverse selection concerns. When you are not a market-maker you have the luxury of “laying in the weeds” until you spot the “wrong” price and then strike.

Vol-adjusted orders

This is an order that pegs your option bid or ask to a model implied vol. So if you are 25% vol offer in that 99 put your offer will adjust upwards if the stock goes down, or lower as the stock rallies. It sounds like a delta-adjusted order but it’s slightly different in that the delta adjusted order has no concept of theta embedded in it.

For example, the vol-adjusted offer will automatically accept a lower price at the end of the day vs the start of the day since a 25% vol option is worth less after time passes.

The delta-adjusted order relies on some underlying model’s delta for price adjustments but it’s not affected by the passage of time (well, technically there is some modest charm effect as time passing infuences delta). A delta-adjusted offer will tend to drift away from being marketable as time passes and theta kicks in, as you are effectively offering a higher IV. Likewise, a delta adjusted bid will become more marketable as time passes which effectively means you are bidding a higher volatility. The vol-adjusted order solves this, but lets the premium float (although these order types can sometimes allow additional constraints).

In general, these types of orders try to limit the adverse selection you are guaranteed when you place an ordinary limit order in options, where you only get filled when the stock moves against you. In fact these are the order types market makers themselves use for streaming logic.

More advanced considerations: “Mark to cross section”

This is one I’ve never seen anyone talk about but it’s obvious once I point it out.

Suppose you are working a large bid using a vol order. You want to pay 25% IV for the 40 strike in XYZ. It’s chipping away little by little and then suddenly you are filled on the entire thing at an average of 24.9% vol.

How do you feel?

Like you always feel when you get filled fast. Like the position is what your one-night stand partner looks like in the morning light. You can’t chew your own arm off fast enough to get out of it.

The first thing you’ll check is whether you got picked off because the stock gapped. But you find the stock hasn’t done anything weird. And then you notice a different chart on your dashboard…

The VIX futures have collapsed in the last 30 minutes.

The reason you got filled on your vega is that vol is much lower across the market. And this doesn’t show up in conventional execution metrics like mark-to-arrival. In fact, you got filled better than your vol limit of 25%.

Your order was recognized and when it was clear that vol was much lower, that any number of vols across the market were a good relative buy compared to what you were bidding, the market maker said “Yours”.

In other words, you wish you could mark your fills to the cross-section of other vols in the marketplace (or at the very least maybe VIX or SPY vol).

This is a whole other layer of attribution. If you sold a basket of vols but SP500 vol was down far more than your basket, do you feel good about your vol-picking skills?

It’s the same issue in active investment management. It’s a waste of time to earn beta. You need to outperform on a risk-adjusted basis to justify effort and identify skill.

Discussion

There isn’t so much a solution to execution as there is an understanding of the levers to think about what approaches work best for you.

At the end of the day, there is a price to entice someone else to warehouse a risk they didn’t wake up asking for. You are trying to execute at the lowest price that satisfies that threshold. Every cent you pay above that threshold is additional surplus to the market-maker above the minimum they require.

You can put out feeler orders on small size to probe how far into the bid-ask they are willing to execute. You are sussing out their edge function. It’s not foolproof. They understand that it’s not worth it to give up that information for small size. They may allow a high stale bid to sit because if they hit it they make a negligible amount of expectancy but what if they leave it there?

Let’s make this concrete with a simple, highly stylized example. An option is worth $1.00, and there’s an opaque distribution around where the next bid might come in, centered at $1.00 ± $0.04. If a one-lot bid comes in for $1.01, the market maker earns one cent in expectancy by hitting it.

But now there’s some chance that the next bid is higher than $1.01. And while that probability is below 50%, the expected bid conditional on waiting may actually be higher than it would have been had the $1.01 bid never appeared. And it might be for a larger size. Depending on what that distribution looks like, the market maker may have more “pot equity” in letting the market remain framed as-is rather than pasting a bid for a single contract.

The more liquid a name is, the less room there is for such games. If it’s highly liquid, there will be enough mm or customer flow to just whack that one lot stray.

The question is always, will I get a better average price in vol terms* if I hit or lift, vs going slowly and giving away info so that the screens mold to me. If trading against your order increases a market-maker’s inventory, they will pad their edge functions even more. If it decreases their inventory, then you probably want more market participants to see it so that it hastens their built-in desire to trade against you. If you want a bidding war for your flow, then you want to make sure everyone sees it. Be more inclined to “advertise” it by showing it as opposed to using electronic eyes (delta orders that are hidden and snipe when a marketable order appears against it).

[*Again, practice proper benchmarking. If I get a good price on my order to buy calls, it could be because the stock fell over the window when I was accumulating them, but on a delta-adjusted basis I could have been getting worse fills on the way down. In other words, I paid more in IV terms.]

Improving execution, to find the minimum edge that someone will accept to trade with you, is a hard problem. At a minimum, I’m trying to help you conceptualize the problem better with respect to adverse selection and the basic hygiene of benchmarking aspects of your fill due to vol changes vs delta. Execution is a classic domain where people do “resulting” where they let their outcomes adjudicate whether they made good decisions. The problem is hard enough without inviting that particular mistake to dinner.