timing the market

how a trader can stop the urge to time the market

In the discord, I was asked a good question that’s lingered for me. I’ll share the fuller response here but first the question:

When you are talking about the ‘mantra’ to reset discipline - “I am buying/selling A for $X because B is $Y bid/offered” - are you thinking in terms of actually putting on both trades or just in pricing terms (that’s expensive and stands in R to this so I am buying this)?

I thought at first that it was the latter you meant but then was thinking that maybe that isn’t actually an expression of the narrow rather than overarching opinion - like I can say I am buying X cheap because Y is expensive to make myself feel good about buying it but it doesn’t really discipline me, whereas the actual long short trade makes me focus on time to expiry, volume, price, trend etc.

Anyway like I say, dumb question but would be very interested to hear the longer form version?

Yea, this is anything but a dumb question. And in case you don’t remember the mantra, it’s what I call a "getting back on track” technique to reset discipline. (thread)

The technique focuses you on relative value. To directly answer the question, I mean that you should stay anchored to the relative lens whether you choose to do both legs or not.

But the unsaid benefit of the mantra is that it recertifies your process. Trading is a business — churning on the basis of discernment that turns over at repeatable time scales.

The loop:

research → opportunity → execution → feedback → adjustment/research 🔁

The loop is wrapped in a risk-management sheath.

In the vol trading context, you are constructing long/short portfolios of options, whether that’s your mandate as a strategy at a fund or a market-maker.

[Some market-makers are more in the category of flipper not warehouser but this business rests on speedy tech more so than discernment of option values].

I would need to fall back on the mantra after getting punished for drawing lines in the sand. Letting my book’s net vega get too long usually because it was so cheap low. Relative value lenses are hard when everything looks cheap or everything looks expensive. Nature of the game. I suspect this is true across many forms of investment not just vol. When discernment of relative value gets hard, we get sloppy. We don’t match the bids we’re getting hit on with enough sells.

This breaks the loop. If you get carried away, we puncture the risk-management sheath as well. Your personality might even change — justifying your position with macro lingo. If you really get desperate, you start blaming the Fed or passive or any other number of things that somehow failed to remind you that nobody owes you the edge you borrowed from the momentary stretch of information and technological track that your career was choo-choo’ing along on.

(Sorry, that got a bit out of hand. I’m sure you’ve never heard anyone sound thaaat entitled, right?)

The mantra stops you from drawing lines in the sand. From turning a relative value game into a…timing game. That’s what an outsize position relative to your business is — a timing bet.

“The cost of wearing this position will be worth it in hindsight because the market will come around to my understanding on a timeline that works for me.”

Timing the general vol level? I’m sorry I haven’t seen this ability consistently from anyone (outside of pockets of legal frontrunning set-ups).

You know what happens when vol gets really low? Trading sucks. And it stays low for so long that you’re happy to dump most of your length by the time it re-traces to your average price. That’s how it goes.

The answer is to take some extra days off when the opportunity cost is low, work on your skunkworks projects, and accept that parsing whether you should sell nominally cheap puts because they “screen high on a percentile skew” basis is an awful way to make a living. If your boss doesn’t understand this, you work for a business manager, not a trader. Masterminding a crap environment is orders of magnitude worse than doing a decent job in a good one.

(Obviously, this comes back to the biggest problem in finance — alignment. The right behavior and the incentives are hard to sync. Not easy to sit on your hands when private school theta is $300 per day per kid.)

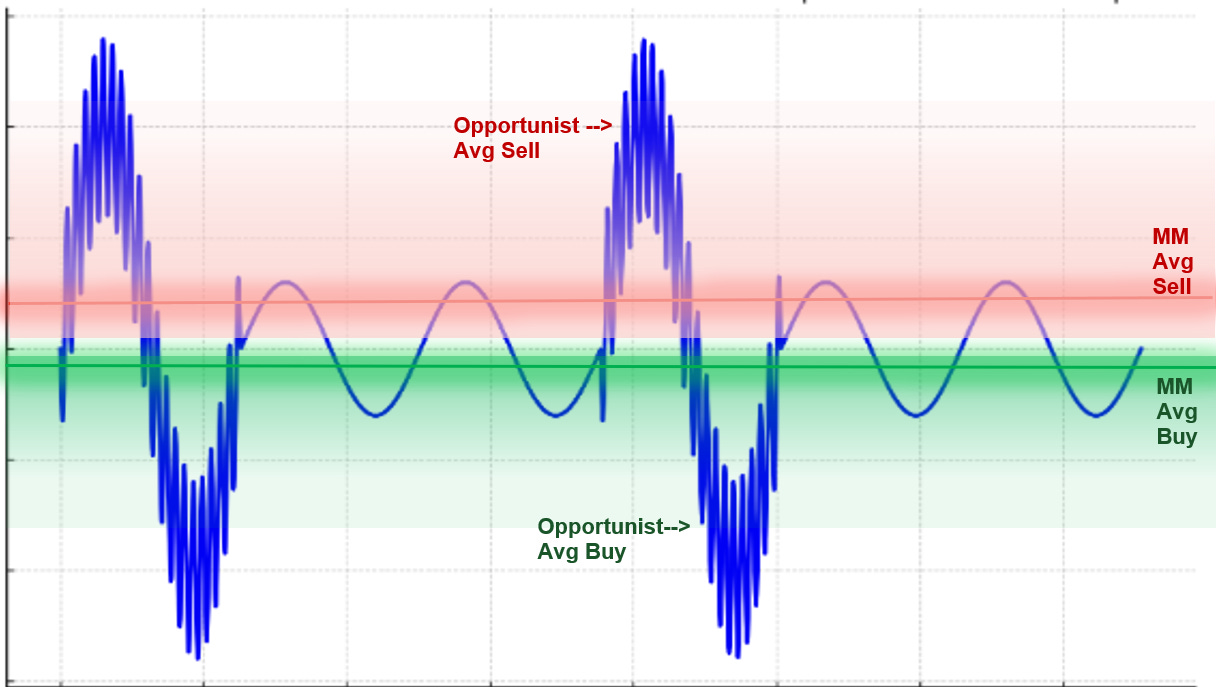

If you have had a consistently profitable trading business, you’ll understand this chart.

The blue line is a unitless version of “cheap/expensive”. It’s a sine wave with the occasional rogue amplitude. Your job is to surf it. Notice that your average buys and sells are not the bottoms or tops, but there is a consistent, albeit un-heroic, profit margin.

The opportunist, perhaps a hedge fund that only looks at your market when it’s stretched, might show up when things get extreme and take a stab. They probably won’t pick the top or bottom, and because the market is especially volatile in that period the position will spend a short time in a sharp drawdown. We can assume this is just a sleeve of their total capital that is otherwise well-diversified.

As a market-maker or trader whose primary business is to surf this particular asset class, you don’t want to turn your business into theirs (especially when I’m being charitable and simply blessing this tourist fund with skill). You have a different set of constraints. They need to bet bigger because they get less swings of the bat in a year, but their opportunity set is broader. They carry a big position across a steep (p/l per unit of time) trajectory.

You’re not here for just the peaks and valleys but you need to be “able” when the market is at the peaks and valleys.

Trading is compensation for a service. In other words, a role. Don’t lose sight of the role. The easiest way to remember that is to ask yourself, “If I’m buying X at this price, what is it cheap against?”

(This will work even if you don’t trade cross-sectionally. If you have a forecast, it will focus you on the forecast’s error bars and the cadence of its feedback.)