seat arbitrage

seat arbitrage and stories

If a tree falls in a forest, does it have a delta impact?

I didn’t feel like writing so you get the answer I’d give over a beer in Roppongi if you gave me a few minutes to collect my thoughts (and if I drank).

Dark arts. Microstructure. Options.

Enjoy…

Another story with some powerful lessons…

Let’s start with one of the best stories I got to be a part of at SIG.

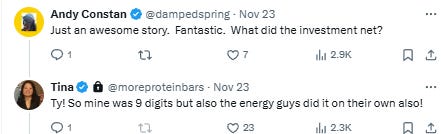

Tina recounted it on Twitter, I’ll offer more color below.

Tina:

Ok, seat arb story. One day, ICE announced that they wanted to buy the NYBOT. Jeff Yass runs into me when he came into the NY office one day when this started, and asked if we should be buying these seats for edge - ICE stock in exchange for seat. I was Head of the NYBOT for SIG at the time with traders in coffee, sugar, cocoa, as well the Russell 1k,2k,3k.

I had talked to many traders beforehand and overwhelmingly, they were against the buyout. So I told Jeff, no it won’t pass and and we would lose buying these seats. Then I dug around more and realized that the vast majority of people against the buyout were leasing the seats and that owners with votes were for.

Called Jeff back and told him I changed my mind. Jeff green lights it. This became such a fun crazy time because, I would be trading during the day, watching ICE stock, watching the seat tape -seat prices on the ticker on the boards, and then when the seat offered were at a sufficient discount, I would stop trading, send my clerk to run to the membership office and bring me docs to sign. The edge from these seats became more than the edge from trading so I would literally stop trading during the day at times to do this. Of course then I had to call Jeff’s right hand man Shawn, and then the COO to free cash up.

We had to put all these seats under individual traders, since technically the traders were the members. So myself, Kris Abdelmessih, etc had many many seats in our names which was also funny. The seats were maybe $650k and I bought maybe 30-40 for SIG.

In the meantime, the CME was also bidding for the NYMEX which was in the same building btw as the NYBOT. Somehow the head of energy for SIG was out for a bit and so I was the most senior in the building. I saw Jeff during that time and he said “ I really really want to buy some NYMEX seats”.

So one day, this guy I knew who owned a clearing company is alone w me at the elevator and asked if I would buy his seat. Jeff had given me a $10m top when the seat was maybe worth $10.8m. Think the displayed market for seats was $8.5 at $9.3m or something. Guy is like, “I will sell you my seat for $8.8m. “

I call Bala [Cynwyd], get his admin, he’s in a meeting but I tell her I needed him. Jeff picks me up, approves it, tells me to call the COO to free margin up and wire the money. Was pretty exhilarating that one trade to get so much edge I must say. The best part was also that, SIG got awarded the CME specialist post on the NYSE so we were the only ones who could sell CME short, setting up for a real arbitrage.

All of this happened when I was pretty young, so you can imagine this was all super cool, the trust Jeff had in me to manage so much of his money. I am forever grateful for the opportunity.

Pretty neat.

I’ll add a bit more.

The head of energy on the NYMEX oversaw nat gas trading as well as me (I oversaw oil trading). Before we came to the NYMEX, he was also my boss on the NYSE. I remember being at the NYSE member meeting when then CEO John Thain (after the Grasso departure) started explaining what would become Reg NMS!

SIG also bought NYSE seats before it went public. By the time, the NYMEX and NYBOT were ready to demutualize they understood this particular style of special sit quite well.

Aside on the NYMEX deal

Before the NYMEX was acquired, it was member-owned. The member owned a “seat” which gave them voting rights as a matter of exchange governance plus the right to trade on the floor.

The CME offered buy the NYMEX in stock. A member would receive some amount of CME shares for each seat they owned. To value a seat you had 2 primary inputs:

- The amount of CME shares you get x the price of the shares during some fixing window (I don’t remember the details)

- The value of the permit which allowed you to trade on the floor

The permit could be valued by a simple DCF based on how much you could lease a seat to a trader or broker on a monthly basis. Forecasting lease rates could be tricky since the life of the trading floor was already in question.

In fact, this is why lessees were so against the deal. They owned no equity in the deal and their livelihood was at risk if the floor’s days are numbered. The seat owners had their golden ticket. In the time leading up to the sale, seats more than 10x’d in value with many seat owners buying even more. That deal spawned lot of generationally rich Sal’s from Staten Island.

The trading permit however was a small portion of the overall seat value so the DCF exercise was fairly inconsequential. The main risk was the CME’s stock price but as you saw from Tina’s story — there was a lot of edge. If CME stock had 30% vol, with the trading permit, you were basically buying the shares at a 1 standard deviation discount (and that’s if you had to hold for a year). With SIG able to short CME to it was a good trade to plow size into.

Being Nimble

You could relate this story back to my video above. There was some opacity to the market because the seat bid/offer prices were maintained by a small group of office workers employed by NYMEX. Our trading assistant would frequently go up to the membership office bearing coffee or treats to chat them up for color on who’s been poking around the order book. Know the chokepoints.

It reminds me of someone who knows their local RE duplex/multi-family market cold. Occasionally a listing comes up and they will know the exact block and layout so they immediately notice that while it says 3 bedroom, it’s really a 4 with a minor change plus it’s on a side of the street worth a 5% bump. Call the broker, offer 50k thru ask if they take the listing down immediately (and this is in the subset of cases where you didn’t get the look before it hit MLS).

Usually this type of fingertip knowledge in dark corners doesn’t scale, but the seat arb was a rare exception. A bunch of jabronis just made their grandkids rich out of the blue and didn’t want to gamble on the closing of the last 20%. Edge.

I think my favorite part of the story though was the moment. We were all in our 20s and Jeff trusted us. SIG was very entrepreneurial. I got to be a member of every exchange in NY except the NYFE in under a decade. You have enough social aptitude plus lots of training in how to think about risk…“go break into that pit”.

Trading firms, at least ones with a floor heritage, have a fairly flat org structure which is strongly on display in Tina’s story. Empowering employees and limiting bureaucracy seems to be a real edge but requires the right culture and alignment. I recently highlighted the flat structure of Valve, but like SIG they don’t answer to any outside investors.

Going from this real-life example up to the level of lesson, this is SIG’s Todd Simkin explaining the advantage in his interview with Ted Seides.

Ted: Over the 30 plus years you've been at SIG, you've seen in the hedge fund world this growth of multi-manager platforms. How do you view yourselves competitively to some of the bigger people that you see in the markets?

Todd: We have been in the fortunate position of having the most patient capital of all. One of the challenges with hedge funds is their need to frequently manage not just quarterly reports but monthly, weekly, or even daily reports. They must demonstrate adherence to their outlined strategy and deliver consistent returns.

In contrast, our investors are the principals of the firm.

They understand the risks we take, including outsized risks, and they are the ones driving these decisions. If I decide to put on a $100 million insurance risk tied to the winner of the Super Bowl, I’m not worried about explaining losses to a multitude of stakeholders. Instead, I have a single conversation with the relevant decision-maker, outlining the edge I perceive and the terms of the deal. Their involvement includes monitoring the situation, such as checking the health of the quarterback throughout the season.

This patient approach has enabled us to stay in and grow businesses during downturns while shutting down exposures when needed. Unlike others who must adhere to predefined strategies, such as maintaining a certain percentage of long-short equity exposure, we can dynamically allocate capital.

We benefit from the large capital base while retaining the flexibility and focus of having a small number of decision-makers. These decision-makers avoid imposing artificial rules that might constrain our strategies, a common issue when managing external money.

Ted: When it comes to trading, even though long-duration capital is an advantage, your focus often remains on relatively shorter time frames. What sets the traders at SIG apart that allows you to stay successful in an extremely competitive market?

Todd: I think there are a few things.

One is that we focus a lot on the decision process—the information available, how we used that information, and then what trade we made—all of that way before we discuss the results. I think a lot of other people have that upside down. They say, "How did you do? If you made money, great, keep doing what you're doing. If you lost money, that means that you took too much risk, and that's a bad thing."

Whereas our traders are focused on the decision process and the expected value first, and because of that, we don't do things that I've seen some of our competitors do that we would think would bleed away some of those profits.

For example, say you do all your work, there's no selection bias, there's no reason to think that you've gained new information by being able to enter a trade and you get to buy an asset for $10 that you think is worth $20. Seems great, and then somebody comes along and they say they'll buy it back from you for $19.

Do you want to sell it?

A lot of people at that point would say, "Well, that's great. I bought it for $10. I sell it at $19. I make $9. I put it in my pocket, and I go away pretty happy, and I sleep well tonight. Nothing bad can happen tomorrow with my position. I'm out of it, and I've just made my money."

And we say, "No." If anything, if we're able to buy more at $19 and we still think it's worth $20, then we would. The fact that we got to buy it for $10 is great, sort of confirmed now by the fact that someone's willing to pay $19, but that doesn't mean we want to sell it and lock in this profit just because you have an opportunity to close a position.

That is part of the culture of the firm. We're not going to give something up just to feel better in our small individual portfolio, which is part of this much, much bigger firm-wide portfolio. If the whole firm had the opportunity to do that and gave up 10% of our profits every time we had a profit-making opportunity, that would be really costly. Somebody else is on the other side of that trade picking up all that extra money that we'd be giving away.

[Kris: That’s exactly the NYMEX/CME example!]

So part of the culture of the firm is one in which we are finding edges wherever we can find them but then capturing all of it by either holding to maturity or holding to expiration or closing at an appropriate rate when we have either new information or where the markets have changed.