Negative Prices Make Sense

How oil tested assumptions that hold most of the time

Negative Prices

Oil prices for the prompt future traded negative this week. Matt Levine covered it well all week, I won’t re-hash. I just wanted to explain negative prices a bit more since it sounds crazy. It’s not. Trader lingo is oil was “trading for a credit”. In other words, you get paid to own it. You get paid to own it because the inconvenience of owning it exceeds its value of using it. If I brought some radioactive uranium to your house you might pay me to take it away. Even if it has lots of value in the right hands.

What are other examples?

- Asbestos. If you google “price of asbestos” you only find prices to “remove asbestos”. This was not always true.

- Old beater cars. My Highlander costs $500 to register every year (thanks California). At some point, the cost to carry a car can be greater than its value. If you couldn’t give it away you are happy to pay someone to take it.

The Wider Lesson of Questioning Assumptions

And if you have failed to examine assumptions in these crazy times you are wasting an opportunity to think outside the box about risk. Interactive Brokers failed to realize futures could trade negative (this oversight cost them $88mm). Well in your model of what a rental property is worth have you considered what happens if a law circumvented limited liability? What if a law changed that made insurers raise prices dramatically or even withdraw from markets? What would that do to affected properties? Modernity if nothing else appears to be hyper-optimization on the stability of assumptions which may turn out to have an expiration. Assumptions that outlive their convenience.

The Curious Case of USO

When it comes to abstractions built on faulty assumptions take a look at the U.S. oil fund more recognizable by its ticker, USO.

Until this week, it held near-dated futures but when those traded as low as $7 a barrel, USO was a few circuit-breakers away from liquidation. Since oil futures we learned can trade below zero, you could argue that USO had about a 25% chance of going bankrupt if you looked at the delta of the 0 strike put.

USO decided to halt trading to announce it would roll into longer-dated futures that were trading near $20. In other words, they changed their mandate (which was legally within their right according to the prospectus) to give themselves more distance from zero. An act of self-preservation that more than halved their chance of going bankrupt.

So the fund managers extended USO’s life. They have a management fee to clip so their motivation is clear. But should USO exist?

USO is a public fund that cannot trade below zero but holds an asset that can. It seems like a mismatch of legal structures. USO posts margin for the oil futures it holds with a portion of the proceeds from what investors have paid for the fund. At negative futures prices USO has no way to collateralize the futures losses since it can not go into shareholders’ pockets for more money.

(Side note: Assuming it doesn’t gap down, my guess is the CME or their clearing broker forces them to delist for cash first. After all, who is on the hook for the future’s losses if the prices go negative if not the shareholders).

Hockey Stick Diagrams

At risk of giving CFA and Series 7 vets PTSD let me use USO to demonstrate optionality. Oil futures can trade negative. USO cannot. If you buy shares of USO and oil futures go negative nobody can ask you for more money. Your shares just go to zero.

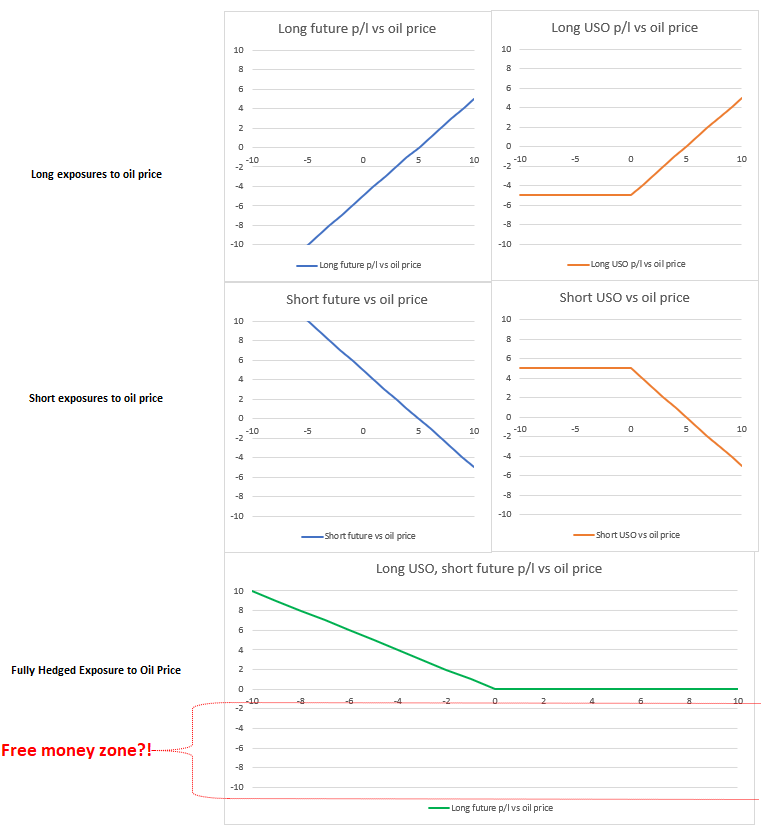

So USO can only go to zero but futures can go negative. For the visual, let’s look at the payoff diagrams.

- In the first pair we look at the payoff of buying oil for $5/barrel using futures OR USO.

- In the second pair we look at the payoff of shorting oil at $5/barrel in both cases.

In the 3rd chart, we take advantage of the fact that USO can only go to zero. Read ahead to see what happens.

A savvy reader will see that the last diagram is the payoff diagram of a put option struck at the zero strike price. And you’ll note that it’s a free option. There’s no oil price at which you lose money.

Well, markets aren’t stupid. USO has been trading at a premium to NAV. Options have premiums.

Questions for advanced readers

1. USO’s premium to NAV has varied greatly this week from 10% to almost 40%. What do you think it’s worth? What drives the fair value of the premium?

2. USO is a basket of futures plus a premium. What does that mean for the volatility of USO? (Hint: there’s some Inception type stuff going on here)

3. The poker question. Can you form a view on USO volatility based on the incentives of the fund? How about the incentives of the risk holders?

Have fun thinking about it. You can share your answers with me but full disclosure, I will not confirm or disconfirm. Your only upside in telling me is I might be impressed.

On Trading and Aptitude

I know there are many younger readers of this letter. I’m not a quant. I took Calculus BC in HS and one stats class in college (although I do want to take more math online — I’m not advocating ignorance). Many of you are very strong in math. There’s a perception that options are about graduate degree stochastic calculus and differential equations. There are research-oriented jobs for which this is true. These jobs require raw mental horsepower and lots of training to tackle technical problems.

On the trading side, don’t get discouraged by academic notation in option papers. Here reasoning and numeracy are the pen and hammer. The tools of the trade. I should add for college students looking to get into trading coding is now table stakes. You need to have something to give in exchange for learning. The business is harder than ever, fetching lunch is not enough. (I know what you are thinking. Every generation in trading always thinks “if I was just born 10 years earlier it would have been so much easier to rake in the bucks”. It’s as stupid as a 300 lb lineman who wishes he could have come up in a time when linemen only weighed 250. He’s committing a time travel fallacy where he gets to go to the past with knowledge of recent innovations in diet, drugs, and exercise). Continuing on. The ability to code is also self-reliance. My own ability is very limited and I’m sure a junior will look at me the way I used to look at older traders who struggled with Excel. Circle of life.

Perhaps more so than the pure quant roles, in trading there’s a lot of room for grit. The analogy is as simple as the fact that most poker players are not quants, but there’s no doubting their discipline, endurance, ability to focus, number-sense, and logic skills. Your liberal arts (and no economics and business degrees are not science) degree is not a life sentence in ops.

(To be clear, this is not an affront to ops…my wife went that way. In fact, there is a whole conversation to be had about why a career in ops can be the more lucrative route. But it’s a parallel route and if a person wants to trade and take risk, anything else will feel like they failed even if objective standards might say otherwise).

On the other hand, tying this all back to the Parable of the Talents essay above — trading is not for everyone. It’s not even for many. You can do anything, except for what you can’t do.