If You Make Money Every Day, You’re Not Maximizing

A treatise on hedging

If You Make Money Every Day, You’re Not Maximizing

This is an expression I heard early in my trading days. In this post, we will use arithmetic to show what it means in a trading context, specifically the concept of hedging.

I didn’t come to fully appreciate its meaning until about 5 years into my career. Let’s start with a story. It’s not critical to the technical discussion, so if you are a robot feel free to beep boop ahead.

The Belly Of The Trading Beast

Way back in 2004, I spent time on the NYSE as a specialist in about 20 ETFs. A mix of iShares and a relatively new name called FEZ, the Eurostoxx 50 ETF. I remember the spreadsheet and pricing model to estimate a real-time NAV for that thing, especially once Europe was closed, was a beast. I also happened to have an amazing trading assistant that understood the pricing and trading strategy for all the ETFs assigned to our post. By then, I had spent nearly 18 months on the NYSE and wanted to get back into options where I started.

I took a chance.

I let my manager who ran the NYSE floor for SIG know that I thought my assistant should be promoted to trader. Since I was the only ETF post on the NYSE for SIG, I was sort of risking my job. But my assistant was great and hadn’t come up through the formal “get-hired-out-of-college-spend-3-months-in-Bala” bootcamp track. SIG was a bit of a caste system that way. It was possible to crossover from external hire to the hallowed trader track, but it was hard. My assistant deserved a chance and I could at least advocate for the promotion.

This would leave me in purgatory. But only briefly. Managers talk. Another manager heard I was looking for a fresh opportunity from my current manager. He asked me if I want to co-start a new initiative. We were going to the NYMEX to trade futures options. SIG had tried and failed to break into those markets twice previously but could not gain traction. The expectations were low. “Go over there, try not to lose too much money, and see what we can learn. We’ll still pay you what you would have expected on the NYSE”.

This was a lay-up. A low-risk opportunity to start a business and learn a new market. And get back to options trading. We grabbed a couple clerks, passed our membership exams, and took inventory of our new surroundings.

This was a different world. Unlike the AMEX, which was a specialist system, the NYMEX was open outcry. Traders here were more aggressive and dare I say a bit more blue-collar (appearances were a bit deceiving to my 26-year-old eyes, there was a wide range of diversity hiding behind those badges and trading smocks. Trading floors are a microcosm of society. So many backstories. Soft-spoken geniuses were shoulder-to-shoulder with MMA fighters, ex-pro athletes, literal gangsters or gunrunners, kids with rich daddies, kids without daddies). We could see how breaking in was going to be a challenge. These markets were still not electronic. Half the pit was still using paper trading sheets. You’d hedge deltas by hand-signaling buys and sells to the giant futures ring where the “point” clerk taking your order was also taking orders from the competitors standing next to you. He’s been having beers with these other guys for years. Gee, I wonder where my order is gonna stand in the queue?

I could see this was going to be about a lot more than option math. This place was 10 years behind the AMEX’s equity option pits. But our timing was fortuitous. The commodity “super-cycle” was still just beginning. Within months, the futures would migrate to Globex leveling the field. Volumes were growing and we adopted a solid option software from a former market-maker in its early years (it was so early I remember helping their founder correct the weighted gamma calculation when I noticed my p/l attribution didn’t line up to my alleged Greeks).

We split the duties. I would build the oil options business and my co-founder who was more senior would tackle natural gas options (the reason I ever got into natural gas was because my non-compete precluded me from trading oil after I left SIG). Futures options have significant differences from equity options. For starters, every month has its own underlyers, breaking the arbitrage relationships in calendar spreads you learn in basic training. During the first few months of trading oil options, I took small risks, allowing myself time to translate familiar concepts to this new universe. After 6 months, my business had roughly broken even and my partner was doing well in gas options. More importantly, we were breaking into the markets and getting recognition on trades.

[More on recognition: if a broker offers 500 contracts, and 50 people yell “buy em”, the broker divvies up the contracts as they see fit. Perhaps his bestie gets 100 and the remaining 400 get filled according to some mix of favoritism and fairness. If the “new guy” was fast and loud in a difficult-to-ignore way, there is a measure of group-enforced justice that ensures they will get allocations. As you make friends and build trust by not flaking on trades and taking your share of losers, you find honorable mates with clout who advocate for you. Slowly your status builds, recognition improves, and the system mostly self-regulates.]

More comfortable with my new surroundings, I started snooping around. Adjacent to the oil options pit was a quirky little ring for product options — heating oil and gasoline. There was an extremely colorful cast of characters in this quieter corner of the floor. I looked up the volumes for these products and saw they were tiny compared to the oil options but they were correlated (gasoline and heating oil or diesel are of course refined from crude oil. The demand for oil is mostly derivative of the demand for its refined products. Heating oil was also a proxy for jet fuel and bunker oil even though those markets also specifically exist in the OTC markets). If I learned anything from clerking in the BTK index options pit on the Amex, it’s that sleepy pits keep a low-profile for a reason.

I decided it was worth a closer look. We brought a younger options trader from the AMEX to take my spot in crude oil options (this person ended up becoming a brother and business partner for my whole career. I repeatedly say people are everything. He’s one of the reasons why). As I helped him get up to speed on the NYMEX, I myself was getting schooled in the product options. This was an opaque market, with strange vol surface behavior, flows and seasonality. The traders were cagey and clever. When brokers who normally didn’t have business in the product options would catch the occasional gasoline order and have to approach this pit, you could see the look in their eyes. “Please take it easy on me”.

My instincts turned out correct. There was edge in this pit. It was a bit of a Rubik’s cube, complicated by the capital structure of the players. There were several tiny “locals” and a couple of whales who to my utter shock were trading their own money. One of the guys, a cult legend from the floor, would not shy away from 7 figure theta bills. Standing next to these guys every day, absorbing the lessons in their banter, and eventually becoming their friends (one of them was my first backer when I left SIG) was a humbling education that complemented my training and experience. It illuminated approaches that would have been harder to access in the monoculture I was in (this is no shade on SIG in any way, they are THE model for how to turn people into traders, but markets offer many lessons and nobody has a monopoly on how to think).

As my understanding and confidence grew, I started to trade bigger. Within 18 months, I was running the second-largest book in the pit, a distant second to the legend, but my quotes carried significant weight in that corner of the business. The oil market was now rocking. WTI was on its way to $100/barrel for the first time, and I was seeing significant dislocations in the vol markets between oil and products¹. This is where this long-winded story re-connects with the theme of this post.

How much should I hedge? We were stacking significant edge and I wanted to add as much as I could to the position. I noticed that the less capitalized players in the pit were happy to scalp their healthy profits and go home relatively flat. I was more brash back then and felt they were too short-sighted. They’d buy something I thought was worth $1.00 for $.50 and be happy to sell it out for $.70. In my language, that’s making 50 cents on a trade, to lose 30 cents on your next trade. The fact that you locked in 20 cents is irrelevant.

You need to be a pig when there’s edge because trading returns are not uniform. You can spend months breaking even, but when the sun shines you must make as much hay as possible. You don’t sleep. There’s plenty of time for that when things slow down. They always do. New competitors will show up and the current time will be referred to as “the good ole’ days”. Sure enough, that is the nature of trading. The trades people do today are done for 1/20th the edge we used to get.

I started actively trading against the pit to take them out of their risk. I was willing to sacrifice edge per trade, to take on more size (I was also playing a different game than the big guy who was more focused on the fundamentals of the gasoline market, so our strategies were not running into one another. In fact, we were able to learn from each other). The other guys in the pit were hardly meek or dumb. They simply had different risk tolerances because of how they were self-funded and self-insured. My worst case was losing my job, and that wasn’t even on the table. I was transparent and communicative about the trades I was doing. I asked for a quant to double-check what I was seeing.

This period was a visceral experience of what we learned about edge and risk management. It was the first time my emotions were interrupted. I wanted assurance that the way I was thinking about risk and hedging was correct so I could have the fortitude to do what I intellectually thought was the right play.

This post is a discussion of hedging and risk management.

Let’s begin.

What Is Hedging?

Investopedia defines a hedge:

A hedge is an investment that is made with the intention of reducing the risk of adverse price movements in an asset. Normally, a hedge consists of taking an offsetting or opposite position in a related security.

The first time I heard about “hedging”, I was seriously confused. Like if you wanted to reduce the risk of your position, why did you have it in the first place.? Couldn’t you just reduce the risk by owning less of whatever was in your portfolio? The answer lies in relativity. Whenever you take a position in a security you are placing a bet. Actually, you’re making an ensemble of bets. If you buy a giant corporation like XOM, you are also making oblique bets on GDP, the price of oil, interest rates, management skill, politics, transportation, the list goes on. Hedging allows you to fine-tune your bets by offsetting the exposures you don’t have a view on. If your view was strictly on the price of oil you could trade futures or USO instead. If your view had nothing to do with the price of oil, but something highly idiosyncratic about XOM, you could even short oil against the stock position.

Options are popular instruments for implementing hedges. But even when used to speculate, this is an instance of hedging bundled with a wager. The beauty of options is how they allow you to make extremely narrow bets about timing, the size of possible moves, and the shape of a distribution. A stock price is a blunt summary of a proposition, collapsing the expected value of changing distributions into a single number. A boring utility stock might trade for $100. Now imagine a biotech stock that is 90% to be worth 0 and 10% to be worth $1000. Both of these stocks will trade for $100, but the option prices will be vastly different².

If you have a differentiated opinion about a catalyst, the most efficient way to express it will be through options. They have the most urgent function to a reaction. If you think a $100 stock can move $10, but the straddle implies $5 you can make 100% on your money in a short window of time. Annualize that! Go a step further. Suppose you have an even finer view — you can handicap the direction. Now you can score a 5 or 10 bagger allocating the same capital to call options only. Conversely, if you do not have a specific view, then options can be an expensive, low-resolution solution. You pay for specificity just like parlay bets. The timing and distance of a stock’s move must collaborate to pay you off.

So options, whether used explicitly for hedging or for speculating actually conform to a more over-arching definition of hedging — hedges are trades that isolate the investor’s risk.

The Hedging Paradox

If your trades have specific views or reasons, hedging is a good idea. Just like home insurance is a good idea. Whether you are conscious of it or not, owning a home is a bundle of bets. Your home’s value depends on interest rates, the local job market, and state policy. It also depends on some pretty specific events. For example, “not having a flood”. Insurance is a specific hedge for a specific risk. In The Laws Of Trading, author and trader Agustin Lebron states rule #3:

Take the risks you are paid to take. Hedge the others.

He’s reminding you to isolate your bets so they map as closely as possible to your original reason for wanting the exposure.

You should be feeling tense right about now. “Dude, I’m not a robot with a Terminator HUD displaying every risk in my life and how hedged it is?”.

Relax. Even if you were, you couldn’t do anything about it. Even if you had the computational wherewithal to identify every unintended risk, it would be too expensive to mitigate³. Who’s going to underwrite the sun not coming up tomorrow? [Actually, come to think of it, I will. If you want to buy galactic continuity insurance ping me and I’ll send you a BTC address].

We find ourselves torn:

- We want to hedge the risks we are not paid to take.

- Hedging is a cost

What do we do?

Before getting into this I will mention something a certain, beloved group of wonky readers are thinking: “Kris, just because insurance/hedging on its own is worth less than its actuarial value, the diversification can still be accretive at the portfolio level especially if we focus on geometric not arithmetic returns…rebalancing…convexi-…”[trails off as the sound of the podcast in the background drowns out the thought]. Guys (it’s definitely guys), I know. I’m talking net of all that.

As the droplets of caveat settle the room like nerd Febreze, let’s see if we can give this conundrum a shape.

Reconciling The Paradox

This is a cornerstone of trading:

Edge scales linearly, risk scales slower

[As a pedological matter, I’m being a bit brusque. Bear with me. The principle and its demonstration are powerful, even if the details fork in practice.]

Let’s start with coin flips:

[A] You flip a coin 10 times, you expect 5 heads with a standard deviation of 1.58⁴.

[B] You flip 100 coins you expect 50 heads with a standard deviation of 5.

Your expectancy scaled with N. 10x more flips, 10x more expected heads.

But your standard deviation (ie volatility) only grew by √10 or 3.16x.

The volatility or risk only scaled by a factor of √N while expectancy grew by N.

This is the basis of one of my most fundamental posts, Understanding Edge. Casinos and market-makers alike “took a simple idea and took it seriously”. Taking this seriously means recognizing that edges are incredibly valuable. If you find an edge, you want to make sure to get as many chances to harvest it as possible. This has 2 requirements:

- You need to be able to access it.

- You need to survive so you can show up to collect it.

The first requirement requires spotting an opportunity or class of opportunities, investing in its access, and warehousing the resultant risk. The second requirement is about managing the risk. That includes hedging and all its associated costs.

The paradox is less mystifying as the problem takes shape.

We need to take risk to make money, but we need to reduce risk to survive long enough to get to a large enough number of bets on a sliver of edge to accumulate meaningful profits. Hedging is a drawbridge from today until your capital can absorb more variance.

The Interaction of Trading Costs, Hedging, and Risk/Reward

Hedging reduces variance, in turn improving the risk/reward of a strategy. This comes at a substantial cost. Every options trader has lamented how large of line-item this cost has been over the years. Still, as the cost of survival, it is non-negotiable. We are going to hedge. So let’s pull apart the various interactions to gain intuition for the various trade-offs. Armed with the intuition, you can then fit the specifics of your own strategies into a risk management framework that aligns your objectives with the nature of your markets.

Let’s introduce a simple numerical demonstration to anchor the discussion. Hedging is a big topic subject to many details. Fortunately, we can gesture at a complex array of considerations with a toy model.

The Initial Proposition

Imagine a contract that has an expected value of $1.00 with a volatility (i.e. standard deviation) of $.80. You can buy this contract for $.96 yielding $.04 of theoretical edge.

Your bankroll is $100.

[A quick observation so more advanced readers don’t have this lingering as we proceed:

The demonstration is going to bet a fixed amount, even as the profits accumulate. At first glance, this might feel foreign. In investing we typically think of bet size as a fraction of bankroll. In fact, a setup like this lends itself to Kelly sizing⁵. However, in trading businesses, the risk budget is often set at the beginning of the year based on the capital available at that time. As profits pile up, contributing to available capital, risk limits and bet sizes may expand. But such changes are more discrete than continuous so if we imagine our demonstration is occurring within a single discrete interval, perhaps 6 months or 1 year, this is a reasonable approach. It also keeps this particular discussion a bit simpler without sacrificing intuition.]

The following table summarizes the metrics for various trial sizes.

What you should notice:

- Expected value grows linearly with trial size

- The standard deviation of p/l grows slower (√N)

- Sharpe ratio (expectancy/standard deviation) is a measure of risk-reward. Its progression summarizes the first 2 bullets…as trials increase the risk/reward improves

Introducing Hedges

Let’s show the impact of adding a hedge to reduce risk. Let’s presume:

- The hedge costs $.01.

This represents 25% of your $.04 of edge per contract. Options traders and market makers like to transform all metrics into a per/contract basis. That $.01 could be made up of direct transaction costs and slippage.

[In reality, there is a mix of drudgery, assumptions, and data analysis to get a firm handle on these normalizations. A word to the uninitiated, most of trading is not sexy stuff, but tons of little micro-decisions and iterations to create an accounting system that describes the economic reality of what is happening in the weeds. Drunkenmiller and Buffet’s splashy bets get the headlines, but the magic is in the mundane.] - The hedge cuts the volatility in half.

Right off the bat, you should expect the sharpe ratio to improve — you sacrificed 25% of your edge to cut 50% of the risk.

The revised table:

Notice:

- Sharpe ratio is 50% higher across the board

- You make less money.

Let’s do one more demonstration. The “more expensive hedge scenario”. Presume:

- The hedge costs $.02

This now eats up 50% of your edge. - The hedge reduces the volatility 50%, just as the cheaper hedge did.

Summary:

Notice:

- The sharpe ratio is exactly the same as the initial strategy. Both your net edge and volatility dropped by 50%, affecting the numerator and denominator equally.

- Again the hedge cost scales linearly with edge, so you have the same risk-reward as the unhedged strategy you just make less money.

If hedging doesn’t improve the sharpe ratio because it’s too expensive, you have found a limit. Another way it could have been expensive is if the cost of the hedge stayed fixed at $.01 but the hedge only chopped 25% of the volatility. Again, your sharpe would be unchanged from the unhedged scenario but you just make less money.

We can summarize all the results in this chart.

The Bridge

As you book profits, your capital increases. This leaves you with at least these choices:

- Hedge less since your growing capital is absorbing the same risk

- Increase bet size

- Increase concurrent trials

I will address #1 here, and the remaining choices in the ensuing discussion.

Say you want to hedge less. This is always a temptation. As we’ve seen, you will make money faster if you avoid hedging costs. How do we think about the trade-off between the cost of hedging and risk/reward?

We can actually target a desired risk/reward and let the target dictate if we should hedge based on the expected trial size.

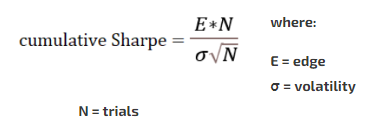

Sharpe ratio is a function of trial size:

If we target a sharpe ratio of 1.0 we can re-arrange the equation to solve for how large our trial size needs to be to achieve the target.

If our capital and preferences allow us to tolerate a sharpe of 1 and we believe we can get at least 400 trials, then we should not hedge.

Suppose we don’t expect 400 chances to do our core trade, but the hedge that costs $.01 is available. What is the minimum number of trades we can do if we can only tolerate a sharpe as low as 1?

Using the same math as above (1/.075)² = 178

The summary table:

If our minimum risk tolerance is a 1.5 sharpe, we need more trials:

If your minimum risk tolerance is 1.5 sharpe, and you only expect to do 2 trades per business day or about 500 trades per year, then you should hedge. If you can do twice as many trades per day, it’s acceptable to not hedge.

These toy demonstrations show:

- If you have positive expectancy, you should be trading

- The cost of a hedge scales linearly with edge, but volatility does not

- If the cost of a hedge is less than its proportional risk-reduction you have a choice whether to hedge or not

- The higher your risk tolerance the less you should hedge

The decision to dial back the hedging depends on your risk tolerance (as proxied by a measure of risk/reward) vs your expected sample size

Variables We Haven’t Considered

The demonstrations were simple but provides a mental template to contextualize cost/benefit analysis of risk mitigation in your own strategies. We kept it basic by only focusing on 3 variables:

- edge

- volatility

- risk tolerance as proxied by sharpe ratio

Let’s touch on additional variables that influence hedging decisions.

Bankroll

If your bankroll or capital is substantial compared to your bet size (perhaps you are betting far below Kelly or half-Kelly prescribed sizes) then it does not make sense to hedge. Hedges are negative expectancy trades that reduce risk.

We can drive this home with a sports betting example from the current March Madness tournament:

If you placed a $10 bet on St. Peters, by getting to the Sweet 16 you have already made 100x. You could lock it in by hedging all or part of it by betting against them, but the bookie vig would eat a slice of the profit. More relevant, the $1000 of equity might be meaningless compared to your assets. There’s no reason to hedge, you can sweat the risk. But what if you had bet $100 on St. Pete’s? $10,000 might quicken the ole’ pulse. Or what if you somehow happened upon a sports edge (just humor me) and thought you could put that $10k to work somewhere else instead of banking on an epic Cinderella story? If St. Pete’s odds for the remainder of the tourney are fair, then you will sacrifice expectancy by hedging or closing the trade. If you are rich, you probably just let it ride and avoid any further transaction costs.

If you are trading relatively small, your problem is that you are not taking enough risk. The reason professionals don’t take more risk when they should is not because they are shy. It’s because of the next 2 variables.

Capacity Per Trade

Many lucrative edges are niche opportunities that are difficult to access for at least 2 reasons.

- Adverse selection

There might only be a small amount of liquidity at dislocated prices (this is a common oversight of backtests) because of competition for edge.

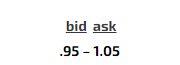

Let’s return to the contract from the toy example. Its fair value is $1.00. Now imagine that there are related securities that getting bid up and market for our toy contract is:

Based on what’s trading “away”, you think this contract is now worth $1.10.

Let’s game this out.

You quickly determine that the .95-1.05 market is simply a market-maker’s bid-ask spread. Market-makers tend to be large firms with tentacles in every related market to the ones they quote. It’s highly unlikely that the $1.05 offer is “real”. In other words, if you tried to lift it, you would only get a small amount of size.What’s going on?The market-maker might be leaving a stale quote to maximize expectancy. If a real sell order were to come in and offer at $1.00, the market maker might lift the size and book $.10 of edge to the updated theoretical value.

Of course, there’s a chance they might get lifted on their $1.05 stale offer but they might honor only a couple contracts. This is a simple expectancy problem. If 500 lots come in offered at $1.00, and they lift it, they make $5,000 profit ($.10 x 500 x option multiplier of 100). If you lift the $1.05 offer and they sell you 10 contracts, they suffer a measly $50 loss.

So if they believe there’s a 1% chance or greater of a 500 lot naively coming in and offering at mid-market then they are correct in posting the stale quote.

What do you do?

You were smart enough to recognize the game being played. You used second-order thinking to realize the quote was purposefully stale. In a sense, you are now in cahoots with the market maker. You are both waiting for the berry to drop. The problem is your electronic “eye” will be slower than the market-maker to snipe the berry when it comes in. Still, even if you have a 10% chance of winning the race, it still makes sense to leave the quote stale, rather than turn the offer. If you do manage to get at least a partial fill on the snipe, there’s no reason to hedge. You made plenty of edge, traded relatively small size, and most importantly know your counterparty was not informed!

As a rule, liquidity is poor when trades are juiciest. The adverse selection of your fills is most common in fast-moving markets if you do not have a broad, fast view of the flows. This is why a trader’s first questions are “Do I think I’m the first to have seen this order? Did someone with a better perch to see all the flow already pass on this trade?”

In many markets, if you are not the first you might as well be last. You are being arbed because there’s a better relative trade somewhere out there that you are not seeing.

[Side note: many people think a bookie or market-maker’s job is to balance flow. That can be true for deeply liquid instruments. But for many securities out there, one side of the market is dumb and one side is real. Markets are often leaned. Tables are set when certain flows are anticipated. If a giant periodic buy order gets filled at mid-market or even near the bid, look at the history of the quote for the preceding days. Market-making is not an exercise in posting “correct” markets. It’s a for-profit enterprise.]

- Liquidity

The bigger you attempt to trade at edgy prices, the more information you leak into the market. You are outsizing the available liquidity by allowing competitors to reverse engineer your thinking. If a large trade happens and immediately looks profitable to bystanders, they will study the signature of how you executed it. The market learns and copies. The edge decays until you’re flipping million dollar coins for even money as a loss leader to get a look at juicier flow from brokers.

As edge in particular trades dwindles, the need to hedge increases. The hedges themselves can get crowded or at least turn into a race.

Leverage

If a hedge, net of costs, improves the risk/reward of your position, you may entertain the use of leverage. This is especially tempting for high sharpes trades that have low absolute rates of return or edge. Market-making firms embody this approach. As registered broker-dealers they are afforded gracious leverage. Their businesses are ultimately capacity constrained and the edges are small but numerous. The leverage combined with sophisticated diversification (hedging!) creates a suitable if not impressive return on capital.

The danger with leverage is that it increases sensitivity to path and “risk of ruin”. In our toy model, we assumed a Gaussian distribution. Risk of ruin can be hard to estimate when distributions have unknowable amounts of skew or fatness in their tails. Leverage erodes your margin of error.

General Hedging Discussion

As long as hedging, again net of costs, improves your risk/reward there is substantial room for creative implementation. We can touch on a few practical examples.

Point of sale hedging vs hedging bands

In the course of market-making, the primary risk is adverse selection. Am I being picked off? If you suspect the counterparty is “delta smart” (whenever they buy calls the stock immediately rips higher), you want to hedge immediately. This is a race condition with any other market makers who might have sold the calls and the bots that react to the calls being printed on the exchange. That is known as a point-of-sale hedge is an immediate response to a suspected “wired” order.

If you instead sold calls to a random, uninformed buyer you will likely not hedge. Instead, the delta risk gets thrown on the pile of deltas (ie directional stock exposures) the firm has accumulated. Perhaps it offsets existing delta risk or adds to it. Either way, there is no urgency to hedge that particular deal.

In practice, firms use hedging bands to manage directional risk. In a similar process to our toy demonstration, market-makers decide how much directional risk they are willing to carry as a function of capital and volatility. This allows them to hedge less, incurring less costs along the way, and allowing their capital to absorb randomness. Just like the rich bettor, who lets the St. Peter’s bet ride.

In The Risk-Reversal Premium, Euan Sinclair alludes to band-based hedging:

While this example shows the clear existence of a premium in the delta-hedged risk-reversal, this implementation is far from what traders would do in practice (Sinclair, 2013). Common industry practice is to let the delta of a position fluctuate within a certain band and only re-hedge when those bands are crossed. In our case, whenever the net delta of the options either drops below 20 or above 40, the portfolio is rebalanced by closing the position and re-establishing with the options that are now closest to 15-delta in the same expiration.

Part art, part science

Hedging is a minefield of regret. It’s costly, but the wisdom of offloading risks you are not paid for and conforming to a pre-determined risk profile is a time-tested idea. Here’s a dump of concerns that come to mind:

- If you hedge long gamma, but let short gamma ride you are letting losers grow and cutting winners short. Be consistent. If your delta tolerance is X and you hedge twice a day, you can cut all deltas in excess of X at the same 2 times every day. This will remove discretion from the decision. (I had one friend who used to hedge to flat every time he went to the bathroom. As long as he was regular this seemed reasonable to me.)

- Low net/high gross exposures are a sign of a hedged book. There are significant correlation risks under that hood. It’s not necessarily a red flag, but when paired with leverage, this should make you nervous.

- Are you hedging your daily, weekly, or monthly p/l? Measures of local risk like Greeks and spot/vol correlation are less trustworthy for longer timeframes. Spot/vol correlation (ie vol beta) is not invariant to price level, move size, and move speed. Longer time frames provide larger windows for these variables to change. If oil vol beta is -1 (ie if oil rallies 1%, ATM vol vols 1%) do I really believe that the price going from 50 to 100 cuts the vol in half?

- There are massive benefits to scale for large traders who hedge. The more flow they interact with the more opportunity to favor anti-correlated or offsetting deltas because it saves them slippage on both sides. They turn everything they trade into a pooled delta or several pools of delta (so any tech name will be re-computed as an NDX exposure, while small-caps will be grouped as Russell exposures). This is efficient because they can accept the noise within the baskets and simply hedge each of the net SPX, NDX, IWM to flat once they reach specified thresholds.

The second-order effect of this is subtle and recursively makes markets more efficient. The best trading firms have the scale to bid closest to the clearing price for diversifiable risk⁶. This in turn, allows them to grab even more market share widening their advantage over the competition. If this sounds like big tech⁷, you are connecting the dots.

Wrapping Up

The other market-makers in the product options pit were not wrong to hedge or close their trades as quickly as they did. They just had different constraints. Since they were trading their own capital, they tightly managed the p/l variance.

At the same time, if you were well-capitalized and recognized the amount of edge raining down in the market at the time, the ideal play was to take down as much risk as you could and find a hedge with perhaps more basis risk (and therefore less cost because the more highly correlated hedges were bid for) or simply allow the firm’s balance sheet to absorb it.

Since I was being paid as a function of my own p/l there was not perfect alignment of incentives between me and my employer (who would have been perfectly fine with me not hedging). If I made a great bet and lost, it would have been the right play but I personally didn’t want to tolerate not getting paid.

Hedging is a cost. You need to weigh that with the benefit and that artful equation is a function of:

- risk tolerance at every level of stakeholder — trader, manager, investor

- capital

- edge

- volatility

- liquidity

- adverse selection

Maximizing is uncomfortable. Almost unnatural. It calls for you to tolerate larger swings, but it allows the theoretical edge to pile up faster. This post offers guardrails for dissecting a highly creative problem.

But if you consistently make money, ask yourself how much you might be leaving on the table. If you are making great trades somewhere, are you locking it in with bad trades? If you can’t tell what the good side is that’s ok.

But if you know the story of your edge, there’s a good chance you can do better.

Footnotes

- Veterans who were trading oil back then might remember how much edge SEM Group spilled into the pit as they martingaled their short vol strategy until they finally blew up. When corporate treasury drones fancy themselves traders the results are predictable

- See Robert Martin’s Option-Implied Probability Distributions for an explainer. I have used butterfly spreads in practice to map distributions. I give an example from the world of natural gas calendar spread options in What The Widowmaker Can Teach Us About Trade Prospecting And Fool’s Gold.

Finally, speaking with On Top Traders Unplugged, vol manager Cem Karsan explains how options are the true underlyer:I’ve said before, and people think I’m crazy, but options are the underlying. It is the full distribution of potential outcomes. Equity values, bond values, asset values are ultimately a summary of much more rich, probabilistic information that lies underneath the surface. And I think that acceptance and understanding are slowly happening not just to institutions, but to human beings. It doesn’t happen overnight. But in a world where we’ve created an ETF and ETN for every style, and every factor, the fact that we’re still betting on up and down, and live in two dimensions is nonsensical. So I very much believe that if you look 20 years in the future, the Option Chains are the underlying. - The slicing and dicing of risk is finance’s salutary arrow of progress. Real economic growth is human progress in its battle against entropy. By farming, we can specialize. By pooling risk, we can underwrite giant human endeavors with the risk spread out tolerably. People might not sink the bulk of their net worth into a home if it wasn’t insurable. Financial innovation is matching a hedger with the most efficient holder of the risk. It’s matching risk-takers who need capital, with savers who are willing to earn a risk premium. Finance gets a bad rap for being a large part of the economy, and there are many headlines that enflame that view. I, myself, have a dim view of many financial practices. I have likened asset management to the vitamin industry — it sells noise as signal. But the story of finance broadly goes hand in hand with human progress. It might not be “God’s work” as Goldman’s boss once cringe-blurted, but its most extreme detractors as well as the legions of “I wish I was doing something more meaningful with my life” soldiers are discounting the value of its function which is buried in abstraction. Finance is code, so if software is eating the world, financialization is its dinner date.

- Standard deviation of binomial distribution = √(n * p * q) where:

n = trials

p = probability of desired outcome

q = 1-p - Since we are getting 4% edge with (near) coin-flip volatility, the prescribed Kelly amount is to bet about 4% of your bankroll.

- See: Why You Don’t Get Paid For Diversifiable Risks and You Don’t See The Whole Picture

- In A Former Market Maker’s Perception of PFOF, I wrote:

How Survivorship Bias Makes Firms Look Like MonopoliesPerhaps I should not be surprised at the monopoly sentiment. Some of you will nod. “How can they make money every day?” First, I’m not sure they do, but even if they did that’s hardly a red flag. Casinos might make money every day so long as they can open. They’re not monopolies. Worrying that financial firms make money every day is conflating market makers with investment managers because they traffic in the same products. But one of them is a customer and the other is a supermarket. With tiny supermarket margins per trade. And high fixed costs. If volumes dried up, the losses would show up even if the margins stayed flat.A stronger, but still naïve argument, that they were monopolies would come from noticing that these shops came of age at the same time as the giant tech firms. This is a hint of how much they have in common. The difference is the size of the relative opportunities, but the tactics are similar.It started with skill and luck. The early big bets on talent and technology meant they were bringing guns to a knife fight. SIG wasn’t known as the “evil empire” on the Amex just because of the black jackets we wore. They understood the risk-reward was completely outsized to what it should be 25 years ago. They were amongst the first to tighten markets to steal market share. They accepted slightly worse risk-reward per trade but for way more absolute dollars. They then used the cash to scale more broadly. This allowed them to “get a look on everything”. Which means you can price and hedge even tighter. Which means you can re-invest at a yet faster rate. Now you are blowing away less coordinated competitors who were quite content to earn their hundreds of percent a year and retire early once the markets got too tight for them to compete.SIG was playing the long game. The parallels to big tech write themselves. A few firms who bet big on the right markets start printing cash. This kicks off the flywheel:Provide better product –> increase market share –> harvest proprietary data. Circle back to start.The lead over your competitors compounds. Competitors die off. They call you a monopoly.