derivative "income" bumhunting

on the popular wave of option etfs

I use the following example all the time because it makes it makes the distinction between premium and income plain.

You’re long a $100 stock.

- It’s fairly priced because it’s 90% to be 0 and 10% to be $1000.

- You overwrite by selling the 500 strike call at $45.

Did you earn income?

A courageous response to my question on Twitter:

There is no problem here. You take your $45 and move on with your life. If you get called away you make 5x, and if your stock goes to $0 you came out with only a 55% loss.

Umm, incinerating money when you think you are investing is actually what I would call a “problem”.

You make $445 10% of the time and lose $55 90% of the time. You are literally better off betting on roulette.

If you overwrite a call that’s actually worth $1 at a price of $.95 because call markets are faded low for sellers, you are stuck with roulette odds. Factor in your brokerage costs (implicitly or explicitly) and effort.

I’d rather get a free hotel room.

As a market-maker when you sell a call you might book the difference between the trade price and what you think the option is worth as “theo p/l”. And even in that case marking-to-model is only going to show a few cents of edge.

Derivative “income” ETFs treat the entire option premium as yield. Guessing disclosure rules prohibit them from selling ITM calls and labeling the intrinsic as yield. Is the distinction that a hard arbitrage bound can’t be marketed as income but a soft one can be? After all, if you buy a .25d call in a random stock for 0, you’re like 99% to make an arbitrage profit with a series of delta hedges. If I sold the call for 1 cent, I can call that yield? Ok. Well, I call that “semantic arbitrage”.

Looking at the AUM growth of these funds, their cheerleading has worked. They don’t need any boosting. Turns out I’ve been collecting the critical takes on these ETFs for a few months. Are they biased? Of course. But I’ll excerpt and weave the arguments so you can form an impression to weigh against what “income” marketers claim.

You will hear the arguments from:

- quants

- a former options market-maker who runs an RIA that uses options

- a very familiar vol manager (who allowed me to re-publish their firm’s take which is nothing short of violence)

- a tax specialist

- a bit from me (and more next week, as I plan to get my hands dirty with some data)

Onwards…

The quants

Roni Israelov and David Nze Ndong’s paper A Devil's Bargain: When Generating Income Undermines Investment Returns was published in the Spring 2024 issue of The Journal of Alternative Investments.

🔗free version of the copy that preceded it on SSRN

These are the key points remixed between me and ChatGPT (emphasis mine):

Passive Income Strategies and Covered Calls

The paper notes that many investors, particularly in the retail sector, are attracted to strategies that generate income, such as covered calls. These strategies have gained popularity due to their ability to provide income through derivative overlays, often being presented as 'income-generating' strategies.

Negative Relationship Between Derivative Income and Total Returns:

The authors demonstrate a strong negative mechanical relationship between the expected total return and derivative income for covered call strategies. Empirical evidence from a nearly 25-year analysis of S&P 500 Index covered call strategies supports this finding. Essentially, the higher the derivative income generated by these strategies, the greater the losses. This outcome contradicts the common assumption that high derivative income leads to higher total returns.

[Kris: This is framed as surprising, but moontower readers know better. Remember Distributional Edge vs Carry?]

Impact of High-Yielding Strategies:

High-yielding call selling strategies, by design, have larger short equity exposure, leading to worse returns. This is a mechanical relationship and is highly predictable. Additionally, selling call options introduces short volatility exposure, which can be profitable but typically does not offset the losses from short equity exposure.

[Kris: Hard to benchmark because the beta is less than the broader index. I’m exploring an adjustment as I want to run my own comparisons. More on that next week inshallah.]

Misconceptions About Covered Calls and “Income”

The authors challenge the idea of treating the initial inflow from selling a call option as income, as this overlooks the associated liability and potential for loss upon settlement of the option. They argue that viewing the initial cash inflow from selling an index call option as income, while ignoring the expected outflow at settlement, is misleading.

[Kris: Been on that train so long I’m slumped over a rocks glass in the bar car right now. And I don’t even drink. See what you made me do. By “you” I mean the committee who defined SEC yield and the asset managers who gave ’em the reach around.]

The quants over at Alpha Architect boosted the paper as well, putting a bow on the argument by comparing the sleight of hand to how dividend chasers are hunted:

Investor Takeaways

Israelov and Ndong’s findings demonstrated that at least some investors might be attracted to covered calls for the wrong reason, seeking income rather than equity and volatility risk premia. That attraction can lead to a misallocation to these risk premia versus a best-fit allocation when analyzed appropriately. They also demonstrated that these strategies might lead investors to have overly optimistic return assumptions guided by their derivative yield. Considering the yield as income could also lead investors to make misinformed choices in terms of spending.

The live returns of the two most popular covered call writing ETFs should cause investors to question the prudence of these strategies, which are also less tax-efficient than traditional long-only strategies.

The most important takeaway is that the call premium is not income. This is the same type of mistake investors make about dividends, leading many to overvalue them. By definition, income increases wealth. Dividends do not do that; when a dividend is paid, their investment is now worth less (by the amount of the dividend). In other words, a dividend is just a forced divestment of some of your investment—you are receiving cash but now have a lower equity allocation. It’s also not income, except for tax purposes, which makes dividend payments an inefficient way to return capital to shareholders. In both cases, the failure to understand this can lead to overallocation to “income” strategies.

Thoughts from former option market maker Mark Phillips

His post is a 5 min read and worth every second but here’s what I want to highlight from Show Me Your Edge (emphasis mine):

The edge [in passive stock index investing] is time. Patience is an expensive virtue - but it pays handsomely in the long run. $1000 a month in an 80/20 stock/bond portfolio for a 40-year career returns about 9.7% a year and turns into $5.3 million. And that’s only half of the monthly 401(k) max limit.

Equity risk premium pays you for your patience. That 9.7% a year is several percentage points higher than risk-free treasury bills because of volatility. Don’t stop buying the few times a decade when stocks drop by more than 20%.

The most naive investor can capture the equity risk premium. It’s available in any brokerage account and with roughly 15 clicks the entire process can be automated.

With equity options, there is no set it and forget it.

There are rapidly increasing number of ETFs that offer options structures in a simple wrapper. But this is grocery store sushi. I’m not so much concerned about them suppressing volatility or creating some sort of derivatives tinder box, as I am with what an undifferentiated approach does for returns.

It takes 15 clicks to set up a lifetime of ERP.

It takes 15 trades to collect a month’s worth of VRP.

The net of the implied vol and historical vol is a very abstract number. Other than over-the-counter agreements in the tens of millions of dollars, that’s not a tradeable concept.

Covered calls are a very simple way to capture part of this. You’re long the equity realized path, and short some implied volatility. But positive VRP could still be a losing trade. Stock going down, even at a lower than expected rate is still negative PnL.

If you can’t trade variance swaps, you can still try and manage a short premium capture strategy with condors, straddles or strangles. Moving these around to stay short the right amount of volatility while stocks move and strikes go in and out of the money is introducing a lot of friction into a trading strategy.

The rebalancing for an index strategy only happens quarterly, and stock execution is cheaper and finer-grained than options execution. This weighting adjustment works very much in the favor of the investor. Outperforming companies are added to, while laggards slowly melt away. Options greeks not only evolve on a daily basis, but the friction and frequency of adjustments are a major performance drag.

Consistently applying the same trade, like a QQQY that sells ATM NDX puts every day, is also going to deliver sub-optimal outcomes. The directional aspect might be a tailwind, but there’s nothing particularly systematic about why that option should be a consistent sale.

Adjusting trades based on delta (i.e. implied volatility levels) is a useful adaptation, but options overlay strategies are more about shifts along the utility curve than adding alpha. Selling calls to buy put spreads transforms the risk, it doesn’t deliver performance.

There are plenty of edges in options, VRP is real…But passive can’t be an edge. Dumping your money in equity markets and closing your eyes will have you beating most active managers. Blind selling or buying options will almost certainly be a performance drag.

Vol manager QVR pulls no punches

As a vol manager themselves, they are biased. And to be clear, so am I. Most of my opinions here overlap (not shocking — with some LinkedIn sleuthing you can spot some personnel merry-go-round between my past firm and QVR although I had no involvement).

Excerpts from their latest letter, DERIVATIVE INCOME…? DEFENSIVE EQUITY…? HEDGED EQUITY…? ARE YOU BEING MISLED?:

The marketing departments at banks and asset managers have conjured up some savvy descriptors for options strategies over the years. Portfolio Insurance, Option Overlay, Hedged Equity, Overwriting, Derivative Income, Defensive Equity, Structured Outcome, Enhanced Equity, and Buffer. As sales departments had success selling these types of products, the assets under management (“AUM”) grew.

Strategies using options are now commonplace in portfolios. Investors will always look for ways to cheapen hedges, but unless very closely understood, persistently capping the upside on your equity allocation is not the answer. Historical techniques such as collars and put-spread collars employed by some of the largest equity providers have become so overcrowded, they will likely lead to nothing but extreme relative underperformance, simply value destruction. This statement is arguably also true for strategies now referred to as “Derivative Income” (aka call overwriting, defensive equity, covered call, etc.), which are all simply selling short calls against equity.

Historically, the go-to benchmark here has been the Cboe BXM Index. An accurate description of benchmarks such as the Cboe BXM or similarly PUT indexes historically would be “Equity-like returns with lower volatility,” but today should be replaced with the statement, “Equity-like risk with lower returns.” These volatility selling strategies cap upside. An option selling strategy is not inherently risk-reducing: a covered call or a cash-secured put selling strategy has effectively the same exposure as outright equities in a sharp market selloff.

Various competitors in Hedged Equity such as JP Morgan, SWAN, Gateway, Calamous, Parametric, and Innovator have had difficulty in recent years delivering their stated objectives. We believe their underperformance is the lack of price sensitivity on the options they use to deliver their stated investment mandate. These strategies have caused a combination of a simple imbalance of near-dated volatility supply and long-dated put demand. Over time, this has led to their products’ underperformance in both market rises and declines. Having simply overpaid for put exposure on the one side and having sold calls too cheap on average on the other side.

So how do investors improve risk-adjusted performance in hedged equity? The answer is: Combine an alpha strategy, that has negative correlation to broader equity. Moving alpha and porting that atop beta has been called portable alpha. Capturing positive returns in upside equity markets (positive up capture) and capturing positive performance or at least flattening downside beta returns in equity downside (flat to negative downside capture) is ideal.

The vast majority of managers are upside down on up-down capture. Hedge funds and various alternative strategies with a negative up-down capture spread, rely on persistent positive equity upside for returns. In other words, this is typically achieved by underperforming funds through a combination of participating in less of the upside (bad) and more of the downside (bad) equating to a negative up-down capture.

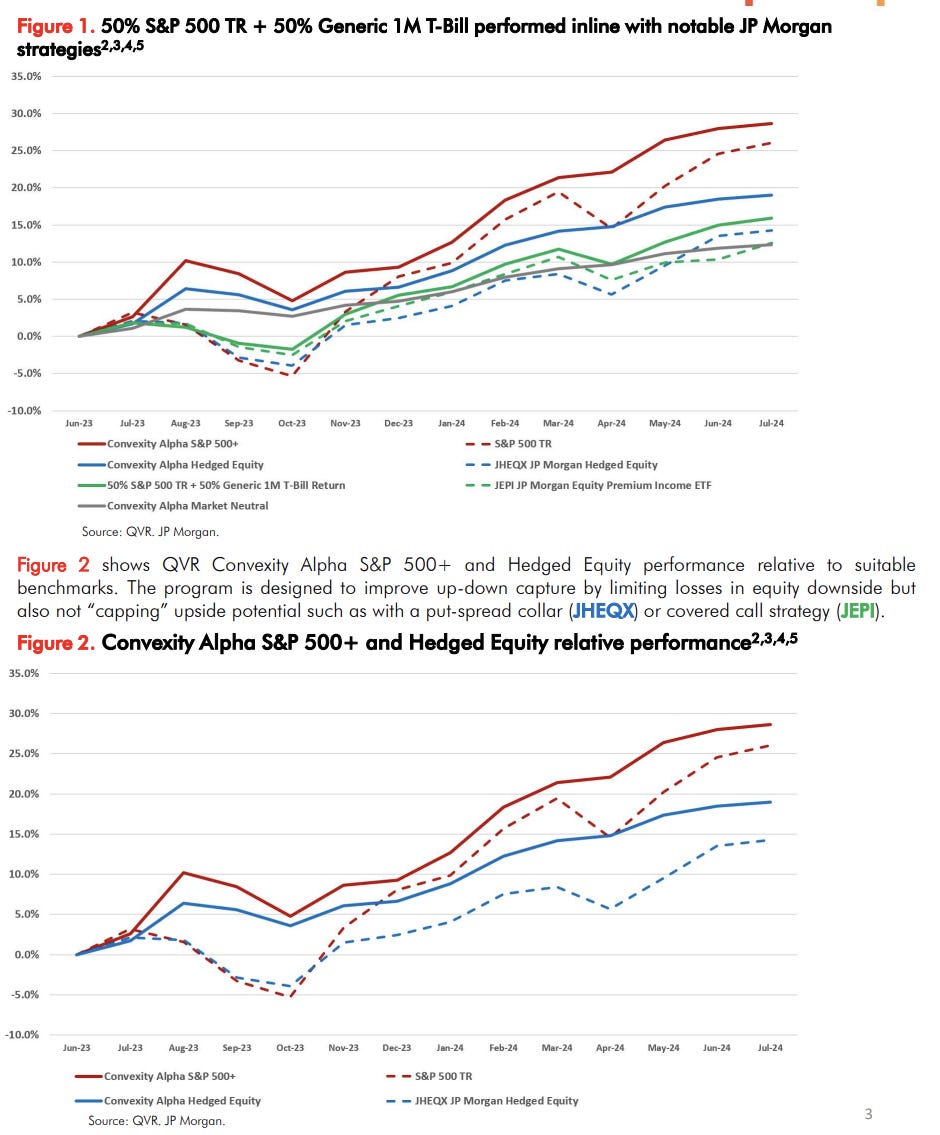

The term “outcome-oriented investing” started to be used many years ago, to allow managers to explain away poor performance relative to simple, suitable benchmarks and strategy substitutes. In Figure 1 we show how a simple strategy substitute of 50% S&P 500 TR + 50% Generic 1M T-Bill Return has recently outperformed notable JP Morgan strategies, tickers JHEQX, JP Morgan Hedged Equity and JEPI, JP Morgan Equity Premium Income ETF. Note the dashed blue and green lines underperforming the 50/50 strategy substitute

The market through option pricing is punishing investors of these products and giving opportunity for more skilled traders to achieve true alpha for investment programs. As a reminder, in decades past these types of strategies had the potential to outperform generic equity benchmarks. Today, however, not even a reduced benchmark hurdle of a 50/50 benchmark seems to be easily outperformed. The massive trade flow, supporting hundreds of billions in AUM growth without a doubt, is contributing to a large and still growing structural dislocation in options markets.

As with all risk premiums, the attractiveness ebbs and flows.

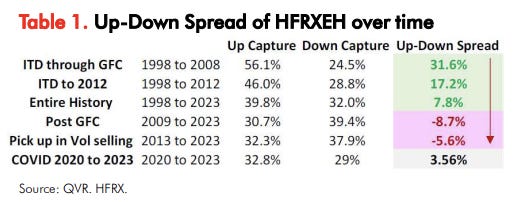

Pre-GFC, short-term options tended to be expensive. As a result, harvesting a volatility risk premium and hedged equity strategies were attractive and backtested well pre-Global Financial Crisis (“GFC”). Post-GFC, both retail and institutional demand for option-selling strategies and hedged equity started to grow rapidly. Large groups of investors are now viewing both as an “evergreen” asset class for income generation (“Derivative Income”) or a liquid alternative (“Hedged Equity”). Or at least that’s what we see marketed everywhere. Table 1 shows the degradation of the up-down capture for the HFRX Equity Hedge Index, +31.6% (excellent) ITD through GFC versus -8.7% Post-GFC (bad)

Call and put write strategies have roughly the same downside risk (down capture) as underlying equity market risk, with much less positive return in up markets. In a portfolio context, adding negative convexity strategies with low returns to the upside and high correlation to risk assets to the downside is not additive to portfolio performance. An investor should always think about the portfolio context and the opportunity cost of capital, the value potential.

Up-down capture is important, not only to produce superior performance but to have any potential of outperforming relevant benchmarks. Or said differently, knowing your manager is not destroying value potential.

So are you being misled, with all the marketing spin? Maybe. This is a market after all and we do encourage different points of view. So here is ours:

- COVERED CALLS ARE NOT A FIXED INCOME ALTERNATIVE

- COVRED CALL AND PUT WRITE STRATEGIES ARE NOT DEFENSIVE EQUITY OR HEDGED EQUITY

- THE VOLATILITY RISK PREMIUM IS NOT PERSISTANTLY POSITIVE OR ATTRACTIVE

- BEWARE OF THE TERM “DERIVATIVE INCOME”, NEW MARKETING SPIN

Opportunity for skilled traders? Unequivocally, yes. And that is the point of this analysis, creating better Hedged Equity and S&P 500 outperformance.

ALPHA MATTERS.

We are undeterred that, finding repeatable sources of alpha, attractive risk adjusted return is best found by providing liquidity to price insensitive end users of derivatives. This is a core belief of any skilled trader and a good starting point for any long-term investment strategy, so should come as no surprise.

A tax specialist’s perspective

Brent Sullivan raises concerns about the return of capital tax hack derivative income ETFs may employ to distribute tax-free income (LinkedIn)

A smattering of moontower thoughts

Options are always about vol. I co-sign both Mark and QVR’s message. No opinion on vol? Then you are just shifting around utility curves. Maybe that’s worth the fees, short-term tax treatment, and execution slippage*.

But “income” is a dead giveaway that someone’s bumhunting.

If the managers want to say they’re in the alpha game and not some poorly-defined risk premia sport then I agree with QVR we should see it in the up/down capture (and that’s what I want to explore more myself).

The broader asset-management and retail world lags the alpha world by a generation. Perhaps in 20 years, any fund focused on options would have to disclose how their vol p/l looks benchmarked to some naive beta-esque expressions of vol trading. Right now you can imagine an option relative value trader in a pod being forced to benchmark their vol buys and sells compared to if they had just bought or sold SPX vol or a basket of liquid singles’ vols in an attempt to measure their vol “idio” or skill. Then you can really study whether they are good at timing, sizing, or selection.

Further reading that drives home the "options are always about vol” message:

- What Part Of Selling Calls Is "Income"?

- Selling Calls: It Might Be Passive, But It Ain’t Income

- A Winner That's Really a Loser

- Dynamic Hedging & Option P/L Decomposition

*Some option traders have mentioned that often the large predictable option fund rebalances will trade mid-market and not even disturb the surface. Well, let’s just say that 20 years ago the market would get leaned the day the makers expected the execution. Today, the table gets set earlier and earlier. The periodicity of maturity cycles and flows makes option traders feel like they’re riding a longboard during the dull times. Slide down a bit, flatten, slope back up the wave, re-catch the energy, make your move, snap back down.

That mid-market execution probably has a few days of slippage baked into it. Harder to detect. But nobody’s job is to stand there and slurp risk for free. Trading firms’ results are coming from someone (actually everyone, but some more than others).