arbitrage is a hall of mirrors

arbitrage-free requirements leads to unintuitive pricing

Given where markets are these days, there are a lot of investors, often former or current employees and execs of Mag7 names that are sitting in large, concentrated position at a low cost basis.

In English, they’re as rich as celebrities but standing standing right next to you giving out Pocky on snack duty for 3rd grade soccer.

They are reluctant to sell because the tax hit is immediate. One possible solution to “have their cake and eat it too” is to stay long but collar the stock. This is typically presented as buying a put option financed by a covered call.

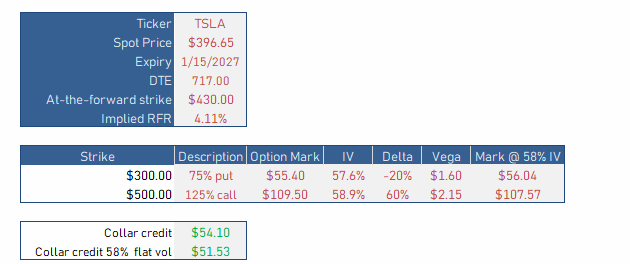

Here’s an example based on closing TSLA option prices on 1/28/2025 for the Jan 15th 2027 expiry (ie 717 DTE).

The stock closed around $396.65.

We can just round numbers, call it $400.

You can buy the 25% out-of-the-money put, the 300 strike, for about $56 and sell the 25% out-of-the-money call, the 500 strike, for about $108.

To be perfectly clear — you can buy the put for protection, sell the upside call and COLLECT about $52 or about 13% premium.

Think about the risk/reward for a moment.

If the stock drops $100 in 2 years you are stopped out at $300 but you collected $52 so your net loss is only $48 or about 13%.

If the stock climbs to $500, you will get assigned on the short call so you’ll make $100 on the long stock position but still get to keep the $52 premium for a total gain of $152 or about 38%.

In other words, you can stay long the stock but you get paid 3x what you lose on a $100 up move vs $100 down move.

It sounds like free money.

The prices come from option theory’s arbitrage-free (ie risk neutral) pricing.

This is a checklist of forces that seem to create the illusion.

✔️The forward price is actually $430

We know that because if you look at the option chain, despite the $430 call being ~ $33 out-of-the-money, it’s the same price as the 430 put which is in-the-money.

The reason for this is because if it didn’t you could put on a reversal or conversion trade to arbitrage the funding rate on the stock.

Think of it this way, if the 430 call cost $20 more than the $430 put you could sell the call, buy the put and collect $20. At expiry, since you are short the $430 synthetic stock you are guaranteed to sell TSLA at $430 (either you exercise the 430 put if it’s ITM or get assigned on the 430 call if it’s ITM). So you can buy the stock today for say $397 which would be a (mostly) riskless position since you are long the stock and short the synthetic. The cashflows would be:

- Collect $20 on the synthetic (remember you sold the call for $20 more than the put)

- Ensure a profit of $33 by expiry (you bought TSLA for $397 and will sell it at expiry at $430)

- Forgo ~$32 interest on $397 for 2 years (assume 4% rfr)

Net arbitrage profit: +$21 in excess of funding costs!

If the 430 call traded $20 UNDER the put you would do the arbitrage in reverse. You’d buy the call, sell the put and be guaranteed to buy the stock for $430 at expiry. To hedge you would short it today at $397 and collect $29 on the cash in your account.

So at expiry you are buying the stock for $430 that you shorted at $397. Cash flows:

- -$33 on buying TSLA synthetically and shorting it today

- +$32 in interest on cash proceeds from the short

- +$20 in option premium (remember, you sold the put $20 higher than the call you bought)

Net arbitrage profit: +$19 in excess of funding costs!

If the RFR is 4% (which it approximately is) then the 430 call and put must traded around the same price for there to be no arbitrage.

Therefore $430 is the 2 year at-the-forward strike.

✔️Despite both option strikes being $100 or 25% away from the spot price, the call is much “closer”

Part of this has to do with the forward being $430. Referencing the 430 strike the 500 strike is only 16% OTM while the 300 strike is now 30% OTM.

The option that is “closer” has a higher delta and worth more due to moneyness.

But the other reason comes from the fact that Black-Scholes assumes a lognormal distribution of returns (which is a positive skew distribution).

Why? If a stock is bounded by zero but has infinite upside the OTM call will be worth more than the equidistant OTM put. The distribution is balanced around a median stock expectation that is dragged lower by volatility (if you make 25% then lose 25% you are net down over 7%).

In TSLA’s case the 300 put has a -.20 delta while the 500 call has a .60 delta!

(TSLA also has an inverted skew — the call IV is touch higher than the put IV but that has a minor effect on the cost of the collar in the context of this discussion.)

Here’s a summary table including the collar price if the IV was the same for the 300 put and 500 call:

💡What this post “encompassed”

If you understand this post you have implicitly reviewed:

- Lessons from the .50 Delta Option (moontower.ai)

- Using Log Returns And Volatility To Normalize Strike Distances (moontower.ai)

- Teaching option basics with live data (moontower YouTube)

- Synthetics: Alternate Realities (Market Jiujitsu)

I called this post “arbitrage is a hall of mirrors” because no-arbitrage pricing theory created this situation where the risk/reward of the collar looks incredibly attractive.

Part of that is theory explicitly incorporates the opportunity cost (the risk-free rate) while our intuition tends to gloss over it. Opportunity cost is an easy topic to understand when someone explains it to them, but it’s trickier to apply in live decision-making scenarios. Look no further than rich people who clip coupons or drive 10 miles out of their way for Costco gas.

The output of arbitrage-pricing can be dissonant to our eyeball tests. It was one of my favorite topics to write about because it does feel so warped.

🟰Understanding Risk-Neutral Probability

This is my guide to the subject. It’s full of nested problems, Socratic method, and even financial theory as philosophy. I’ll re-print one of the nested sections:

👽Real World vs Risk-Neutral Worlds

No-arbitrage probabilities allow us to price options by replication

The insight embedded in Black-Scholes is that, under a certain set of assumptions, the fair price of an option must be the cost of replicating its payoff under many scenarios. Any other price offers the opportunity for a risk-free profit. Have you ever wondered why the Black Sholes “drift” term for a stock is the risk-free rate and not an equity risk premium (like you’d expect from another type of pricing model — CAPM) or the stock’s WACC? A position in a derivative and an opposing position in its replication is a riskless portfolio. Therefore that portfolio only needs to be discounted by the risk-free rate. Option pricing derived from a no-arbitrage replication strategy means we should use the risk-free rate to model a stock’s return.

‼️What seasoned option traders get wrong: Outside of the option pricing context, the risk-free rate is the wrong assumption for drift!

From Philip Maymin’s Financial Hacking:

One of the most common mistakes that even highly experienced practitioners make is to act as if the assumptions of Black-Scholes (lognormal, continuous distribution of returns, no transactions costs, etc.) mean that we can always arbitrarily assume the underlying grows at the riskfree rate r instead of a subjective guess as to its real drift μ. But this is not quite accurate. The insight from the Black-Scholes PDE is that the price of a hedged derivative does not depend on the drift of the underlying. The price of an unhedged derivative, for example, a naked long call, most certainly does depend on the drift of the underlying. Let's say you are naked long an at-the-money one-year call on Apple, and you will never hedge. And suppose Apple has very low volatility. Then the only way you will profit is if Apple's drift is positive; suppose Apple has very low volatility. Then the only way you will profit is if Apple's drift is positive…if it drifts down, your option expires worthless. But if you hedge the option with Apple shares, then you no longer care what the drift is. You only make money on a long option if volatility is higher than the initial price of the option predicted. The drift term of the underlying only disappears when your net delta is zero. In other words, an unhedged option cannot be priced with no-arbitrage methods

💡Takeaway: Arbitrage Pricing Theory

Sometimes called the Law of One Price, the idea contends that the fair price of a derivative must be equal to the cost of replicating its cash flows. If the derivative and cost to replicate are different then there is free money by shorting one and buying the other. This approach is how arbitrageurs and market-makers price a wide range of financial derivatives in every asset class including:

- Futures/Forwards

- Options

- ETFs and Indexes These derivatives are the legos from which more exotic derivatives are constructed.

A Source of Opportunity

Let’s recap the logic:

- Arbitrage ensures that the price of a derivative trades in line with the cost to replicate it.

- A master portfolio comprising:

- a position in a derivative

- an offsetting position in its replicating portfolio

- This master portfolio is riskless.

- A riskless portfolio will be discounted to present value by a risk-free rate otherwise there is free money to be made.

- The prevailing prices of derivatives imply probabilities.

- Those probabilities are risk-neutral arbitrage-free probabilities.

But those probabilities don’t need to reflect real-world probabilities. They are simply an artifact of a riskless arbitrage if it exists.

This can lead to a difference in opinion where the arbitrageur and the speculator are happy to trade with each other.

- The arbitrageur likely has a short time horizon, bounded by the nature of the riskless arbitrage.

- The speculator, while not engaging in an arbitrage, believes they are being overpaid to warehouse risk.

Examples

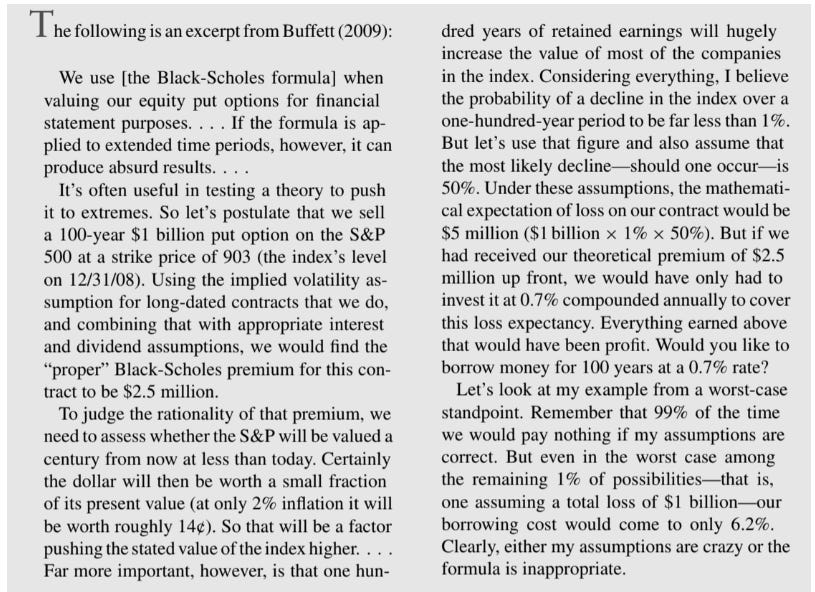

1) Warren Buffet selling puts

The Oracle of Omaha engages in oracular activity — not arbitrage. Warren is well-known for his insurance businesses which earn a return by underwriting various actuarial risks. Warren is less famous for his derivatives trades. [The fact that he rails against derivatives as WMDs might be the most ironic hypocrisy in all of high finance but as I always say — we are multitudes.] Like his insurance business, the put-selling strategy hinges on an assessment of actuarial probabilities. In other words, he believes that real-world probabilities suggest a vastly different value for the puts than risk-neutral probabilities. The major source of the discrepancy comes from the drift term in Black Scholes. Warren is pricing his trade with an equity risk premium in excess of the risk-free rate that a replicator who delta hedges would use.

The option traders who trade against him can be right by hedging the option effectively replicating an offsetting option position at a better price than the one they trade with Berkshire. Warren is happy because he thinks the price of the option is “absurd”. In Warren Buffett is Wrong About Options, we see this excerpt from a Berkshire letter during the GFC:

Jon Seed writes:

Warren’s assumptions aren’t crazy. In fact, they seem to be pretty accurate. As Robert McDonald derives in the 22nd Chapter of his 3rd addition of Derivatives Markets, a 100 year put for $1bn assuming 20% volatility, a long-term risk free rate of 4.4% and a dividend rate of 1.5% implies a Black-Scholes put price of $2,412,997, close to Buffett’s $2.5 million. But Warren isn’t discussing risk-neutral probabilities, those assumed in Black-Scholes and imputed by volatility assumptions. He’s evaluating the model’s probabilities as if they were real, actual probabilities. If we, (really Robert McDonald), evaluates Black-Scholes using real probabilities by also incorporating our best guess of real equity discount rates, we see that the model is consistent with Warren’s common sense approach. Assuming stock prices are lognormally distributed and that the equity index risk premium is 4%, we would substitute 8.4% for the 4.4% risk-free rate, obtaining a probability of less than 1% that the market ends below where it started in 100 years. Buffett also assumes that the expected loss on the index, conditional on the index under-performing bonds, will be 50%. This again is a statement about the real world, not a risk-neutral world, distribution. With an 8.4% expected return on the market, the implied expectation of $1 billion of the index conditional on the market ending below where it started is $596,452,294, or 59.6% of the current index value. Again, this is close to Buffett’s assumption of 50%.

2) FX Carry

FX futures are derivatives. Their pricing is a straightforward output of the covered interest parity formula. I think I learned this concept on the first day of trader class back in the day.

The key to the formula is recognizing that the value of the future is just the arbitrage-free price arising from the difference in deposit rates between the 2 currencies in the pair.

If a foreign currency offers a higher interest rate than a domestic currency, you expect its future to trade at a discount. We won’t bother with the math since the intuition is sufficient:

If you borrowed the domestic currency today to buy the foreign currency so you could earn the yield spread for say 1 year, you’d have a risky trade — you’d be exposed to the foreign currency, and its associated interest income, devaluing when you try to convert it back to the domestic currency.

therefore, to make the trade riskless, you need to lock in the forward rate today by selling the future. You know what that means — you expect that forward rate to trade at the no-arbitrage price

The higher-yielding currency must therefore have a lower forward FX rate.

The carry trade is basically a speculator saying:

“I know the future FX rate should trade at a discount to the spot rate but I’ve noticed that the future rate rolls up to converge to the spot rate, rather than that lower rate being a predictor of the spot FX rate in one year.

So I’m going to buy that FX future and hold it for a profit.”

The carry trade is not an arbitrage or riskless profit. It’s a risky profit. But the opportunity arises because the futures contract would present an arbitrage at any price other than the risk-neutral price.