another XIV brewing in crypto?

long shot bets against MSTR

If you don’t know what MicroStrategy (MSTR) then congrats, you have won life. Close this tab and go back to sliding down rainbows and swimming with otters.

For those who remain you likely know that Saylor has been financing his BTC purchases from sale of convertible bonds.

I have nothing to add to that conversation but I have a trade idea. It’s gonna take some background to build up to it.

First, there are 2 required reads. They aren’t long and they’re excellent. The best combination. I will highlight some key points from them.

Convert of Doom: Microstrategy and the dark arts of 'volatility arbitrage' (6 min read)

by Alexander Campbell

This post explains how Saylor is effectively arbitraging the MSTR’s volatility by issuing convert that pay zero interest. This works because a convert is just a bond with an embedded call option. By delta hedging the implied vol in the embedded option, dealers or investors can earn a return if the realized vol exceeds the implied vol. The expected return presumably compares favorably or at least similarly to if MSTR just issued interest-bearing debt but Saylor, is effectively transmuting volatility into interest payments.

[In general, when a convert is first issued it’s common for both the stock and vol to decline as dealers hedge both the delta and often the implied vol by selling long-dated options to offset some of the vega they’ve bought at a discount.]

Campbell is both educational and insightful showing how:

1) the Merton model can be used to understand why MSTR is so much more volatile than BTC — the MSTR’s premium to NAV is positively correlated to BTC!

(In Battle Scars As A Call Option, I explained how one of my most painful trades occurred when I was long UNG vol when it went premium to NAV. In that case, the sizeable premium was inversely correlated with the price of gas. The exact opposite scenario of MSTR’s juiced vol today!)

2) this is a regulatory arbitrage.

Quoting Campbell:

Result: Retail buys MSTR shares at 150% premium while sophisticated investors arbitrage vol differentials and MSTR books the diff between all these trades as profitable transactions.

Here's the irony: We require hedge funds to register with the SEC, spend $50-500k annually on compliance, and limit themselves to accredited investors with millions in the bank. Yet retail investors can freely buy MSTR shares through Robinhood.

And therein lies all the difference. There’s nothing wrong with what MSTR is doing, but it’s a good example of the law of unintended consequences.

Regulators block retail from 'risky' hedge funds while inadvertently pushing them into something potentially more dangerous.

By restricting crypto access for years, regulators left retail investors few options. Bitcoin futures required $300k contracts with 50-100% margin. ETFs were obscure or nonexistent. So people bought MSTR instead - a far more complex and potentially risky vehicle.

In trying to protect retail investors, the SEC has inadvertently funneled them into a potentially much riskier product.

Which brings us to the next required reading:

Moonshot or Shooting Star? A Volatile Mix of MicroStrategy, 2x Leveraged ETFs and Bitcoin (7 min read)

by Elm Wealth

Oh how I love the existence of levered ETFs on concentrated ideas. This post echoes a very real possibility of XIV’s “volmageddon”.

Something we’ve discussed ad nauseum in this letter is volatility drag and how geometric returns diverge much lower from arithmetic returns as we increase volatility. The divergence is proportional to variance or volatility squared.

The article links to a neat calculator which offers hands-on lesson in volatility drag.

💡Learn more💡

- A Simple Demonstration of Return Vs Volatility

- The Volatility Drain

- Well What Did You “Expect”?

- Geometric vs Arithmetic Mean In The Wild

- Path: How Compounding Alters Return Distributions

And linking these to options which is where we are heading:

Exponents are good, wholesome fun. And this post was certainly that, inspiring the the trade idea we’re building towards.

The long quote below (emphasis mine) cuts to the heart of the matter.

Now let’s use some data to look at the probability of going bust just from a single really bad day. The price of a 2x leveraged ETF should go to zero if the price of the stock underlying the ETF goes down by 50% or more in a single day. The probability of such an event is a function of the variability of the MSTR stock price. If we assume the volatility of MSTR will be about 90% (or 5.6% per day), then we could think of a 50% decline in the stock price in one day as being a roughly 9x daily volatility move. A natural question is how often do stocks with very elevated variability, like MSTR, experience days when they decline by 9x their daily variability in returns?

We looked at about 1500 US stocks over the past 50 years, chosen so that at some point they were within the top 1000 stocks by market-cap. We found that the annual probability of such stocks experiencing a one-day price decline of 9x daily volatility was about 6%.

[Kris: The fatness of the tails should swipe you like a dragon. In Mediocristan, 9 standard dev moves don’t happen.]

This isn’t quite the final answer though, as we need the probability of a stock dropping by that much some time during the day, rather than just close-to-close. The usual estimate for the probability of touching a level over some time interval is to simply double the probability of being below that level at the end.

[The explanation of this is the same logic we’ve discussed whereby we estimate the probability of a one-touch by doubling the delta. Here’s Elm Wealth explaining:

To see why this is true in a simple random walk without drift, note that for every path that finishes below the level at the end of the period, there is another path where it hit the level and then followed a path that was a mirror of the path that finished below the level. So, for every path that finished below the relevant level (here a 50% drop), there’s another path that touched the level but then reflected and wound up above the level at the end.]

So, assuming MSTR volatility of 90% per annum, the probability of a down 50% intra-day move occurring at least once over the next year is about 12%.

If we use the MSTR volatility implied by the options market of 160%, then down 50% is only 5x daily volatility. The same data as above yields a close-to-close annual probability of about 30%, which we estimate as about a 60% probability of an intra-day drop that would send the ETF to 0.

There are a number of alternative perspectives one could take in trying to estimate this probability: for instance, trying to estimate the probability of a large one-day drop in Bitcoin and how that might impact the MSTR premium to BTC. For example, a 25% one day drop in BTC and a 33% collapse of the MSTR premium would imply a 50% drop in the MSTR share price.

[Kris: This hints at the MSTR premium vs BTC correlation Campbell wrote about]

A more complex analysis might try to estimate whether it is possible for these leveraged ETFs to become large enough that their daily rebalancing trades could themselves drive the price down 50% in one day. For example, imagine that MSTR rapidly triples in price due to some combination of BTC rally and an increase in MSTR’s premium to the BTC it owns, and the assets in the MSTR leveraged ETFs go from $5 billion to $30 billion. The market capitalization of MSTR could be about $270 billion and the leveraged ETFs would be owning $60 billion, or 22%, of MSTR stock outstanding.

Now imagine for some reason, MSTR stock drops 15% during the day – which, given MSTR volatility, would not be unusual. The leveraged ETFs would need to sell $9 billion of MSTR stock at the closing price. Recently, MSTR daily average trading volume at the close of the day has been about $2 billion, so this would be quite an impactful amount of MSTR to sell at the end of the day. For every 1% the price declines further than the 15%, the ETFs will need to sell another $500 million of MSTR, and if that pushes the price down by another 1%…well, you can see this doesn’t have a happy ending for owners of the leveraged ETF or MSTR.

[Kris: see The Gamma of Levered ETFs]

Bottom line, we think there’s a pretty decent probability – somewhere in the range of 15% to 50% – that these 2x leveraged MSTR ETFs are effectively wiped out in any given year if they are not voluntarily deleveraged or otherwise de-risked sooner.

Towards a trade idea

The 2x ETF is MSTU and the 2x inverse ETF is MSTZ. Unless these are delevered, if MSTR [falls/rises] by 50% in one day [MSTU/MSTZ] goes to zero.

I’m going to walk you through my stream of consciousness as I reached the end of the article.

1) I’ll accept Elm Wealth’s logic , my first question is…um, are there options listed on the levered ETFs?!

Checkmark✔️

MSTZ is thin but MSTU has over 350k contracts of OI.

2) We are not in Kansas anymore. The distribution is extremely discontinuous.

On a hellacious down day in BTC coinciding with premium compression (that positive correlation that Saylor has been monetizing being his undoing is the kind of poetry markets like to write) and the telegraphed, reflexive ETF rebalance flows can take MSTU straight to zero XIV style.

And this can happen on any day.

3) So the next thought in the chain was to consider buying 0DTE puts. Like every morning before brushing my teeth.

This is a non-starter for 2 reasons.

i. 0DTEs are not listed on MSTU

ii. ODTEs don’t capture the overnight vol so you don’t own “all” the risk. This is especially important in BTC since it’s a 24 hr market.

4) We’ll come back to the question of expiry. I’m just adhering to the sequence of my thinking for better or worse (feel free to debug my mental compiler).

So what strike do I want? The bet only hinges on a Boolean outcome — did MSTR fall 50% or not?

If the thrust of the trade is so starkly binary then the put I want is lowest strike on the board that you can pay a penny for. I only care about maximum odds. The strike is the payoff, the premium is the outlay. So if I buy the $5.00 put for a penny I get 499-1 odds.

[Since we are thinking in a risk-budgeted binary way rather than in continuous option terms, a parallel framing would be the $5/$0 put spread]

It’s worth noting that this is a bit weird compared to typical investment scenarios. You really only care about the distance of the strike from 0 which determines the payoff and the premium. The price of the stock doesn’t matter because your payoff depends on a certain percent move happening. No matter what nominal price MSTU trades for, if MSTR goes down 50% MSTU gets wiped out.

Let’s start by thinking aloud about constructing a bet and work from concrete to abstract before we bring it back to concrete again.

Buying a 2-week put

Suppose you spend $1,000 2x per month to buy puts that cost $.01.

(Because of the 100x multiplier this translates to 1,000 option contracts)

If you are buying the $2.50 strike, you will get paid $250,000 if MSTU hits zero.

Over the course of the year, following this strategy will cost $24,000 ($1000 twice a month).

Say it hits on the last trial, your net profit is $226,000 (payoff - cumulative outlay). Call it 9-1 odds.

If MSTU has a 10% chance of hitting zero within the year, this is a fair bet. If the probability is higher, you have positive edge, lower you have negative edge.

This a good place to pause for birthday problem math. It allows us to convert into a useful unit of probability per day.

MSTU trades 251 days a year. If we think it’s 10% to hit 0 one of the days we can compute the probability of it NOT hitting zero on any given day like this:

(1 - p²⁵¹) = 10%

p = 99.958%

Converting to odds:

.99958 / ( 1- .99958) ~ 2382

The odds against MSTU hitting zero on a random day is 2382-1.

If there were 0DTEs if you could buy say any strike from $24 or higher for a penny you would have edge to your model probability of “There’s a 10% chance that MSTU hits zero this year”.

Using the daily probability to compute the chance of MSTU going to zero in 10 business days (roughly what a 2-week option encompasses).

1 - .99958¹⁰ = 99.581% or 238-1 odds.

If you can buy a 2-week $3 strike put for a penny you’d have edge to this probability.

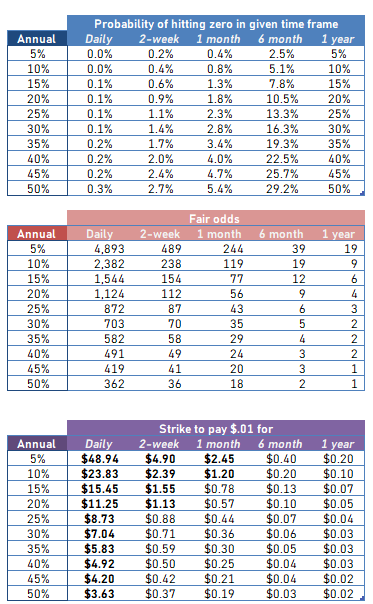

We can extend the reasoning above to construct useful tables based on a range of assumptions about the “probability of MSTU going to zero with a year”.

Let’s step through an example.

If you believe MSTU has a 20% chance of going to zero in a year, then you need to 56-1 odds on a 1-month put for it to be fairly priced (and assuming the ETF getting zero’d is the only way to win).

[To compute the payoff ratio: strike / (strike - premium)]

If you could buy the 1-month $.57 strike (yes, a very low strike!) for a penny you would get the 56-1 odds.

I started with this whole “what option can I pay a penny for” reasoning because my intuition told me that for a trade like this you will want a strategy that trades an a very near-dated option for a teeny price because that’s probably where you are going to find the best odds in this framework.

But I should not get to anchored to either this penny idea or the notion that the near dated is absolutely the right way to play this.

At this point, it’s time to look at some data to see if:

1) the prices are ever attractive

2) can we narrow down an expiry range

Market prices

The first thing I did was pull up an option chain for the regular monthly expiry — Jan2025. Good news. While the far OTM puts markets are sometimes wide, several strike are 0 bid, offered at $.05 but critically last sale is $.01. There’s someone who sells these things for a penny.

[This is not the case for the puts in the less liquid MSTZ double short ETF. The markets are also much wider. What does this tell you?]

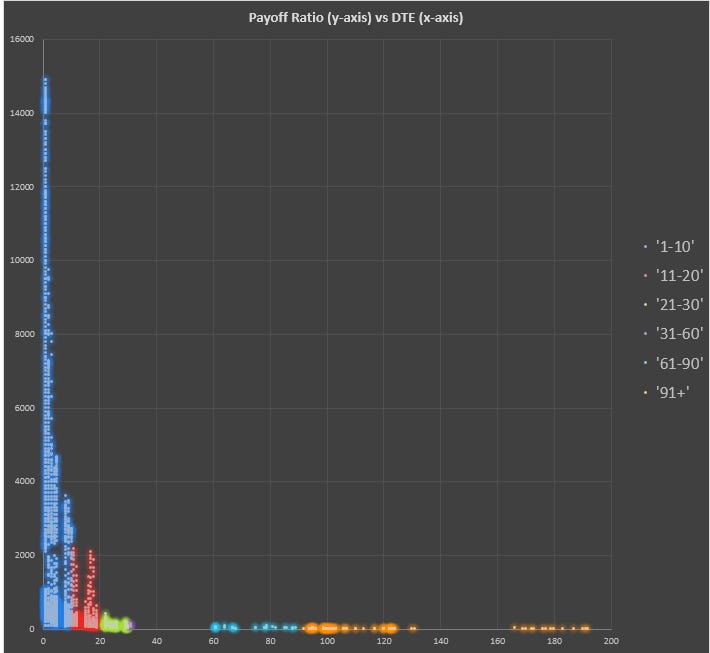

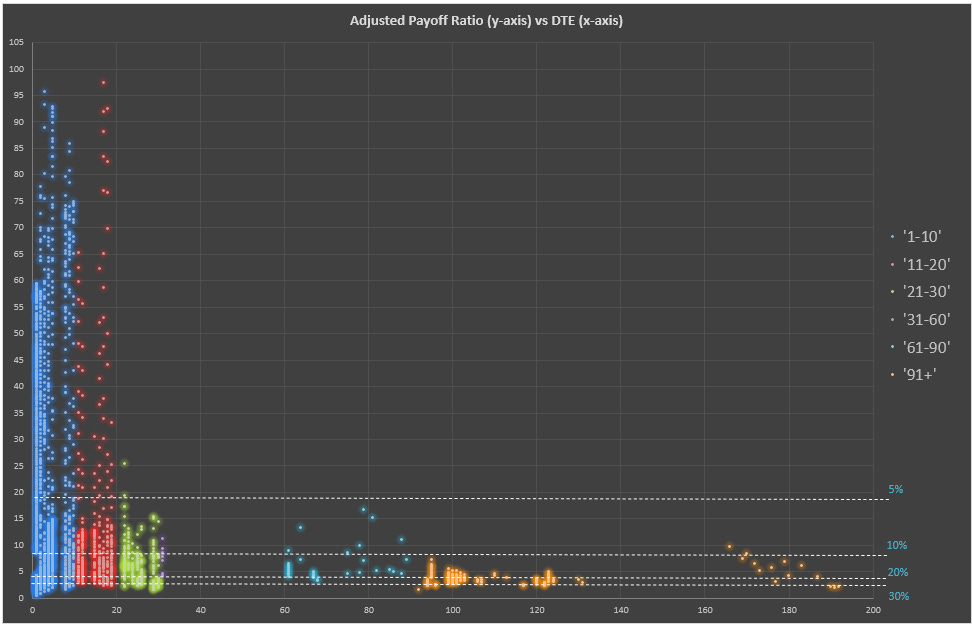

I fetched fitted end-of-day put prices for MSTU options from 9/24/24 to 1/6/25, filtering for all puts below 1.5 delta. FAR out-of-the-money puts (the puts that correspond to the 98.5% call).

- I computed the payoff ratios for all puts less than 1.5 delta by comparing strike and premiums as explained earlier.

- The color coding corresponds to expiry buckets in calendar days (ie 1-10, 11-20, etc)

- I added a penny to all the premiums. So an option fitted to be $0 is marked at $.01

Right away 2 things stand out:

- The chart has trash scaling because of point #2

- As expected, you are going to get much better payout ratios on near-dated options. If there’s 2 DTE and the stock is $100, buying the $50 put for a penny offers 4999-1 odds.

So the intuition about the near-dated being better bang for the buck seems correct but the scaling is obscuring the picture and there’s another problem (we’re going to get to it but if you feel up to it, try to guess what it is. One hint is it’s not about transaction costs. That’s important and I’ll say a word about it later as well but that’s not the angle here.)

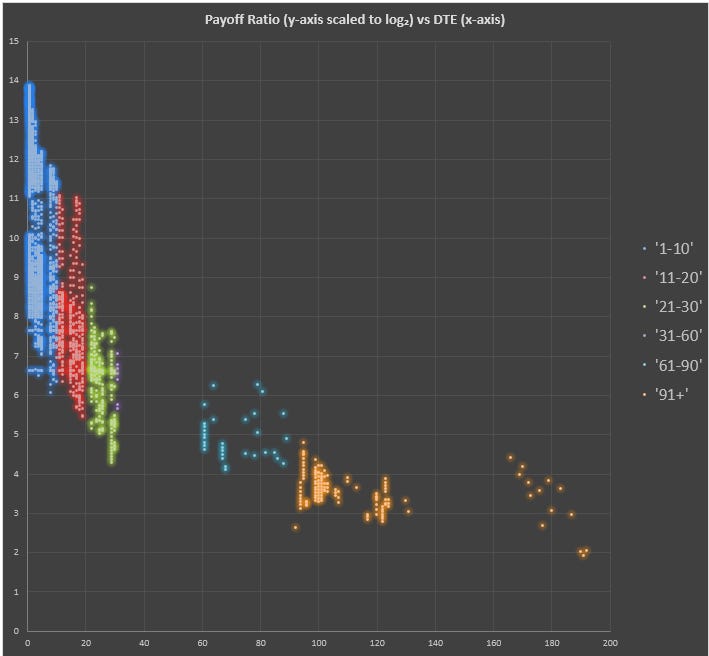

Let’s fix the scaling. Log base 2 compresses this range nicely and is easy to interpret (every tick mark doubles the payoff).

Ahh, much better. Now we see a smooth descent of payout ratios. To be clear, a y-value of 10 is 2¹⁰ or a payoff ratio of 1024-1. An 11 is 2048-1, and so forth.

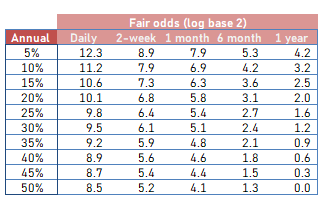

Here’s the payoff table reproduced in log base 2 terms:

You can see how the puts suggest the market thinks the probability of MSTU disappearing is somewhere in the 10-15% range (but probably less since you can win on the puts without the ETF zero’ing).

The risk/reward on these near-dated puts is much higher than the deferred puts which is expected since we require much higher odds. Remember if we thought that there’s a 10% chance of MSTU zero’ing in a year, a $10 strike put can trade for $1 (ie 9-1 odds) and be fairly priced. But these short-dated options need to offer much better odds to compensate for a much smaller probability window of MSTU going under.

We need to compare the payoff ratios with the probabilities we inferred from the annual probability (the birthday math) for the stock zero’ing in 1 week, 1 month, etc.

But before that we can address the mystery problem.

By comparing the strike & premiums we can identify if an option is cheap or expensive compared to our model probability but we can’t assess the validity at the strategy level. In other words, we can’t answer whether it’s better to spend $24k on long-dated puts or $2k a month on 1-month puts.

To handicap that we need to adjust our payoff ratios by how often we need to trade so that we can now compare all the strategies on the same measuring stick — “if my annual probability of MSTU zero’ing is X, what’s the best approach”.

So we divide the payoffs by the number of times you must trade per year.

[Used some simple rules, ie for 1 dte, we divide by 251, for 30 dte by 12]

We don’t need to use log scaling for the strategy level chart.

The way to read this is if you think the annual probability is greater than say 20% (see the horizontal dashed lines) than all opportunities above the line are positive expectancy. There’s a lot more opportunity in the nearer-dated confirming the original intuition but every now and again it looks like a 2-3 month put gets fairly cheap.

The median payout ratio normalized to annual odds is 7-1 or 12.5% implied probability of MSTU offing itself.

In summary:

- MSTR is highly volatile

- If it moves 5-10x it’s daily standard deviation in one day to the downside, MSTU can go to zero.

- Those size moves historically (via Elm’s article) happen about as often someone rolls a 10 with 2 dice if we say MSTR is 100 vol. If we use it’s implied vol which is more forward looking, we’re it’s more like rolling a 7.

- The market seems to price the puts in-between those possibilities but we see that the price moves around quite a bit so you can scoop some when they get offered cheap.

- The more aum MSTU gathers the larger the end of day rebalance trade. Something to keep in mind.

Keeping a close eye on this, perhaps building a monitor around this idea is a nice way to grab a convex outcome. Especially one that I suspect has reflexive properties that are conservatively ignored in this independent events “birthday math”.

Endnote on execution

I assumed $.01 slippage on these options. If you pay $.02 for an option that we computed the payoff based on a penny, you’re getting half the odds. So when talking about really long odds and teeny probabilities and option prices, costs matter. Regardless, you have all the knowledge you need to compare max payoff to your own execution prices to bridge this fully to reality.