American options are not vanilla

American options as "optimal stopping time" problems

I’ve always found it amusing that the most commonly traded options, American-style equity options contracts, are considered “vanilla”. Because they can be exercised early, their valuation is an instance of a famously difficult problem — explore/exploit. The only reason I might refer to them as “vanilla” is not for them being simple, but simply common.

The last time you bought a TV you encountered this problem — do I keep researching or pull the trigger? From shopping or channel-surfing to giant commitments like who to settle down with or businesses to pursue, the problem sits at the heart of decision-making across all domains though it tends to be more formally considered in fields like computer science, finance, game theory, and operations engineering.

💡See my notes from Brian Christian talking about Algorithms to Live By to see how explore/exploit is seen in everything from “bandit” problems to child development and learning strategies.

The Black-Scholes formula is elegant. It’s a closed-form equation that you can implement in a common financial calculator. As trainees, we programmed it into our bootcamp standard-issue 12C:

But Black-Scholes doesn’t work for American-style options.

💡If you need accessible, non-formal refreshers on Black-Scholes, see:

- The Intuition Behind The Black Scholes Equation

- A Visual Appreciation For Black-Scholes Delta

- Slides to Moontower’s The Equation That’s a Strategy

The equation is a factory — it takes in raw material and squeezes out a hot dog on the other side. But it has no visibility on the path between input and output. But that path is key to the core question:

What is the optimal stopping time of an American-style option?

When should we exercise the right to “stop” the option early?

While American options let you exercise anytime before expiration, you usually shouldn’t. The value of optionality (your right to wait) is typically greater than the small benefit of early exercise.

This discussion is not only useful but fun since we invoke microeconomics in real-life.

It starts with 2 key questions.

WHY would you exercise early?

- Puts: to collect interest sooner on the short stock position.

- Calls: to capture a dividend

WHEN is it worth it to exercise early?

We check 2 tests in sequence:

a) Is the benefit worth more than the optionality you give up?

Compare the gain from early exercise to the value of the out-of-the-money option at the same strike.

Examples:

- Put: If a stock is $100 and you own the 120-put, you can exercise the right to sell/short the stock at $120. Is the interest you earn on the $120 until expiry worth more than the 120-call, which you are effectively selling at 0?

- Call: Let’s say this $100 stock pays a $1 dividend and you own the 80-call. Is the 80-put, which you are giving up, worth less than the dividend?

The cost of the exercise (the time value of the option) vs its benefit (interest or dividend) is just the first step. But now you need to zero in on the when.

This is where we have to go to “marginal” cost/benefit. In other words…

b) Is one day’s cost of waiting (theta) greater than one day’s benefit (interest or dividend)?

When daily theta decay exceeds daily interest/dividend gain

Let’s get more concrete.

Stepping through the tests

We start with assumptions.

✔️Stock price = $100

✔️DTE = 60

✔️RFR (the rate you earn on cash in your account) = 5%

✔️Implied volatility = 20%

✔️ No dividends

We will analyze the 105 strike put.

I used a Black-Scholes European style calculator to compute the option values. You’re supposed to use an American calculator, but since I’m trying to explain the exercise rules, that would mask some exposition. Pointing out the European calculator’s mistakes will be better for learning.

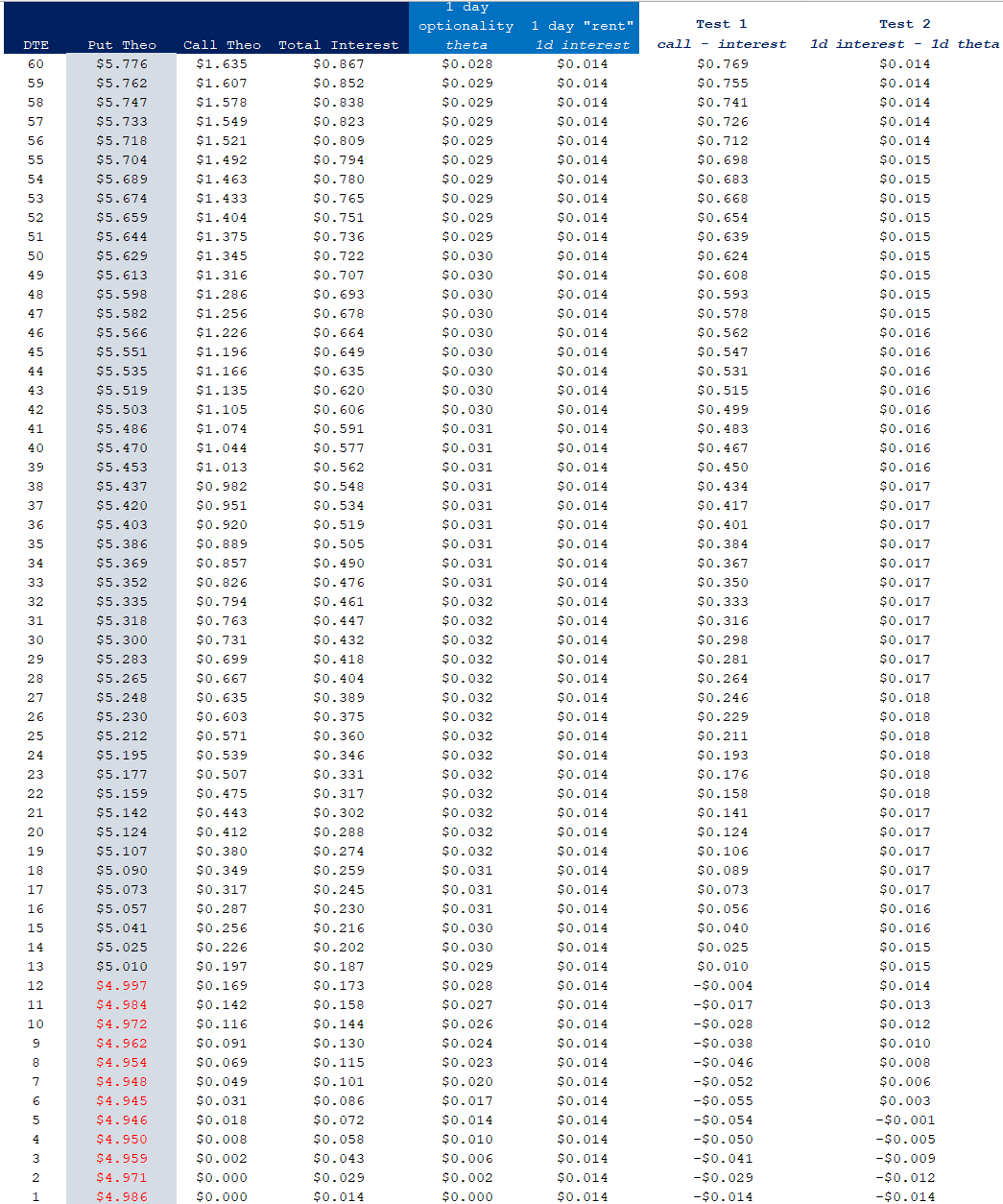

Ok, we start with this table of our option values for each day until expiry.

Column explanations:

- Put theo: Black-Scholes value for the 105 put given our assumptions

- Call theo: Black-Scholes value for the 105 call given our assumptions

- Total interest: interest you’d collect until expiry if you exercised the right to sell shares at $105. Computed as 105e^(.05 * DTE/365) - 105

- theta from the option model

- 1 day’s interest computed as 105e^(.05 * 1/365) - 105

- Test 1: value of the call - total interest. This is a blunt total comparison of the put I own’s time value (represented by the call) vs the interest I’m forgoing by not exercising

- Test 2: 1 day interest that I forgo vs 1 day optionality represented by theta. This represents the marginal comparison of the interest vs optionality for 1 day.

At 12 DTE, the European model is telling us that the 105 put is worth LESS than its intrinsic value of $5. That’s a clue!

That’s the point at which the time value of the put (ie represented by the call on the same strike…remember put/call parity means the call is “in” the put) is LESS than the interest you’d earn if you exercised early.

💡The European put can and will trade under intrinsic. The American-style option should not trade less than $5 because if it did, you would simply buy the put, buy the stock, exercise immediately and have a risk-less profit of the amount it traded under intrinsic. So if for some reason you could buy the American-style 105 put for $4.92, you’d buy the stock for $100, then exercise the put which allows you to sell the stock at $105. Between the stock and put you’ve laid out $104.92 but your proceeds from the sale are $105. You pocket $.08 with no risk.

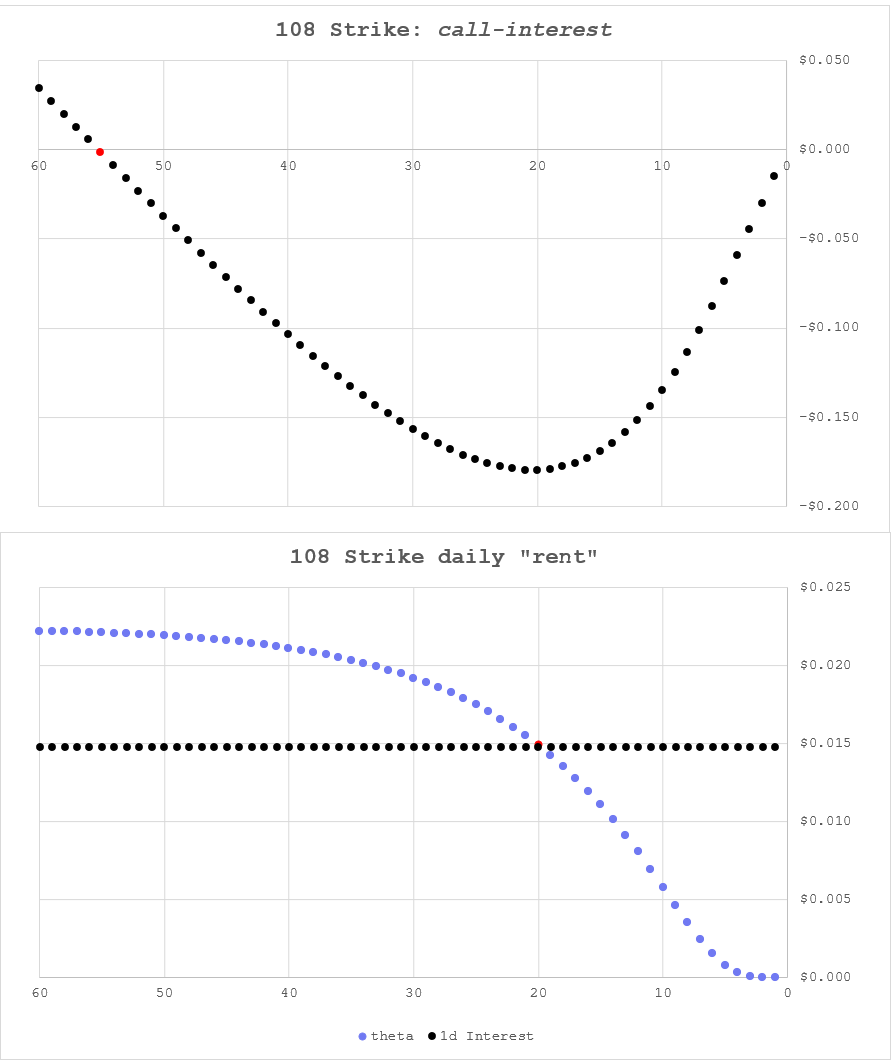

At 12 DTE, the 105 put has passed Test 1 (interest > option value). Visually, you can see this on the upper chart. But look at the lower chart…

The lower chart is the visual of Test 2 (1-day interest exceeding 1-day optionality).

5 DTE is the point of optimal early exercise.

Let’s do this again a bit faster with the 108 strike.

Since this put is deeper ITM, the corresponding 108 call is headed to zero earlier and the interest one earns on $108 is a bit more than the interest on $105 so without working through any math we expect to exercise the 108 put sooner than 5 DTE.

For the 108 strike, Test 1 (total interest exceeds the call value) is satisfied with 55 days until expiry, but the optimal exercise point isn’t until 20 DTE.

Interest “rent” is constant; theta is NOT

The daily interest benefit is linear. It’s basically total interest divided by DTE. But you may have noticed the theta values are curved. It’s intuitive that theta for an ATM option increases in an accelerating way until expiry. After all, with 1 DTE, the ATM option is entirely extrinsic value and you know in 24 hours the time value goes to zero.

For the 108 call, it has no value several days before expiry so there’s nothing to decay. The option went through the steepest part of its depreciation days earlier. Test 2 depends on when 1d interest and 1 theta “cross”.

For reference, this is a visual of theta vs DTE for strikes of various moneyness. Remember, the stock is fixed at $100. The closer the option is to ATM, the later it experiences its steepest decay. With a week to go, the far OTM 109 call has no decay. It’s already worthless.

Optimal exercise of American calls

You exercise calls early to capture a dividend. You must be the shareholder of record on the “record date” to be entitled to the dividend. When the stock goes “ex-dividend” it means any holders of the stock are NOT entitled to the dividend.

Owning a call option does not give you rights to the dividend since you are not a shareholder. That’s why the cost-of-carry component of option pricing discounts calls by the amount of the dividend.

When a stock goes “ex”, meaning the dividend has been paid out, the shares fall by the amount of the dividend which makes sense — the balance sheet has shed X dollars per share of cash.

The owner of the call will experience the drop in share price without any dividend receipts to make up for it.

💡If a $100 stock pays a $1 dividend and the shares open at $100 your brokerage or data vendor will say the stock is up $1 on the day. Unchanged would mean the stock should open at $99. If you own a dividend-paying stock it’s not “extra” return. The company just chiseled off a piece of its value and gave it to you in cash. It’s economically a wash. If they didn’t pay you the cash the company would retain it, the enterprise value would be unchanged and your return is the same. Your cash flow is different but of course you could have sold 1% of your shares to the same effect. In fact, that’s more tax-efficient. Of course, these are all first-order mechanical considerations. The properties of companies that pay or don’t pay dividends is a separate point of debate. If you do not believe stocks fall by the amount of the dividend, meet me at the corner of Trinity and Rector. I’ll be in a trenchcoat with a suitcase of Euro-style call options to sell you on a lovely selection of fat dividend yield aristocrats.

The optimal exercise of ITM American calls is easier. Test 1 is simple. Is the dividend I’m receiving greater than the value of the OTM put I’m giving up? [Again the put value tells me the time value or optionality of the ITM call I actually own]

What about the optimal timing of the exercise?

The marginal thinking represented by Test 2 is straightforward. The benefit of exercising the call early is discrete — it’s a dividend on a specified date. If the dividend is worth more to me than the time value of the call, I shouldn’t give up the time value until the last moment I have to capture the benefit. I should exercise on the day before the stock goes ex-dividend so I’m the shareholder of record.

Real-world considerations

- Early exercise decisions are directly dependent on interest rates (for puts), dividend amounts (for calls) and volatility (which influences the optionality you are surrendering when you exercise the option). Just think of the benefit you receive vs what you are giving up and what influences those quantities.

- Stock settles T+1. If you exercise a put on Thursday, your short share proceeds from the stock hit your account Friday, meaning you collect interest over the weekend. When I started in trading, stock settlement was T+3, so Tuesdays were “put day”. That’s the day you’d exercise to capture interest over the weekend. From 2017 to 2024, “put day” was Wednesday as the standard settlement was T+2. Microstructure nerds might be aware of a famous pick-off trade in the early aughts where a SIG alum bought shares from a NYSE specialist requesting T+1 settlement knowing that the company was going to pay a giant special dividend the next day. This ended up being very expensive to the seller. And eventually, to the buyer as this maneuver landed them in court. The option world is littered with dividend shenanigans. The range of ethical codes is wide and can certainly extend to “a moral obligation to relieve dumber people of their money” or “legal fees are part of my expected value calculation”. Having spent time in the trading world, I’m not surprised to when I notice these familiar moralities in tech, but a distinction in trading is pro vs pro violence was ok, ripping off customers was killing the golden goose.

- Sometimes companies announce a large dividend suddenly that the exchange will treat as special. Strike prices will be revised lower to account for the special dividend keeping the economic impact on options unchanged. That said, incremental changes in dividend policy are risks to option holders. Increased dividends lowers calls/raises puts all else equal.

We have an option calculator that allows you to compare the “early exercise premium” of American to European options:

https://www.moontower.ai/tools-and-games/option-pricing-calculator